General Info

Free with Museum Admission

Free for Members

Fossils Tell Stories

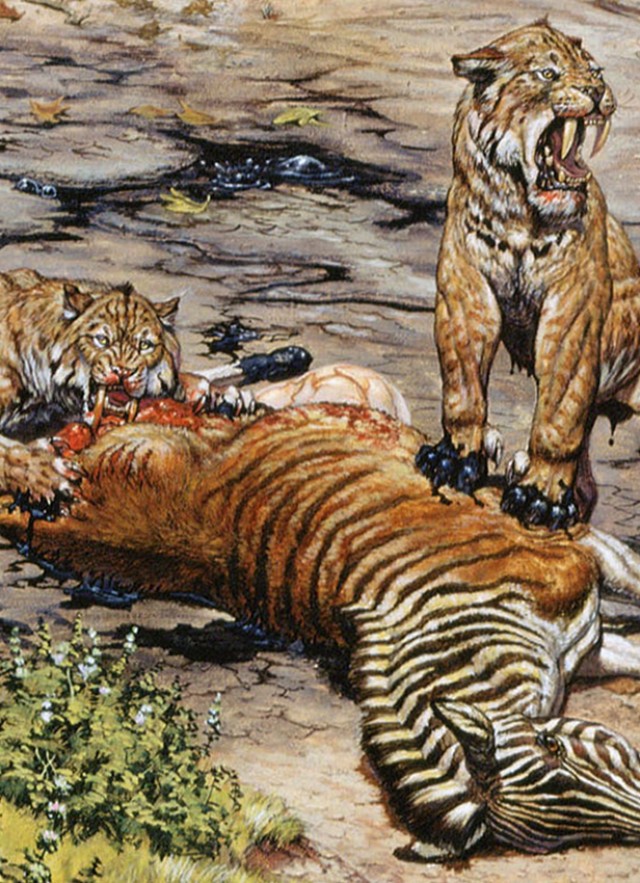

If you were standing in the middle of Hancock Park in Los Angeles 40,000 years ago you might witness a family of saber-toothed cats triumphantly sharing a kill. How do we know they fed this way and were not lone hunters? Fossils! Fossil evidence can reveal how ancient animals behaved. Discoveries like this one, however, do not happen overnight. It can take many years and countless professionals to piece the story together.

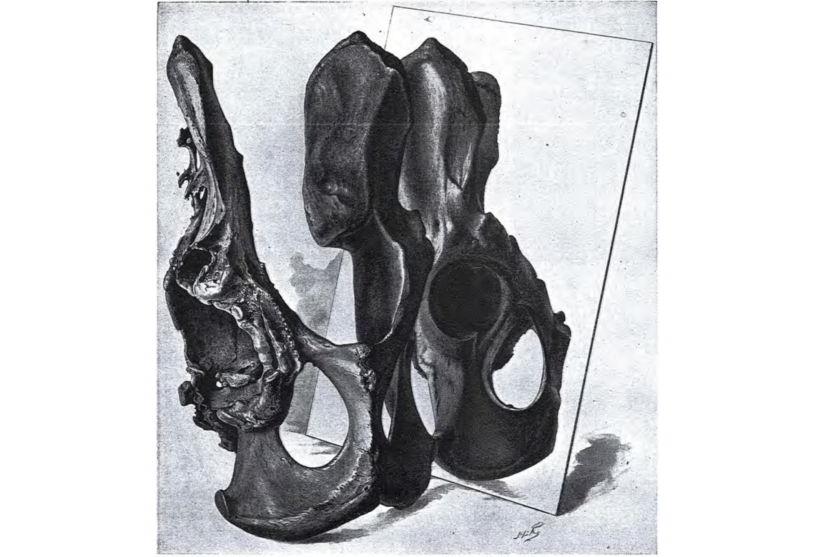

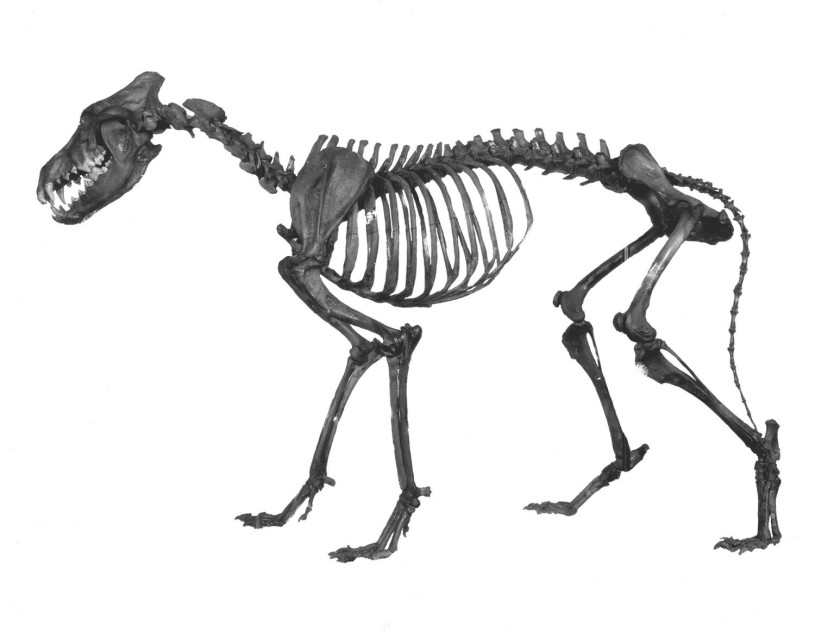

This particular mystery began in 1914 when excavators at Rancho La Brea (now La Brea Tar Pits) started digging up an astonishing number of Ice Age fossils, from saber-toothed cats and mammoths to birds, snakes, and even ancient tree branches. One set of saber-toothed cat hip fossils—a pelvis and a thigh bone—appeared different from the others they had found. The left side of the hip was rough, jagged, and very strangely shaped.

In the 1930s, a scientist named Roy Moodie took an interest in the strange fossils, noting that the pelvis was the most strikingly abnormal object in the collection of Rancho La Brea fossils. Based on the evidence available at the time, Dr. Moodie thought the cat might have suffered a hunting injury that became badly infected. He felt this could explain the dramatic shape of the bones and published a paper with his hypothesis.

Ancient Bones Meet Modern Medicine

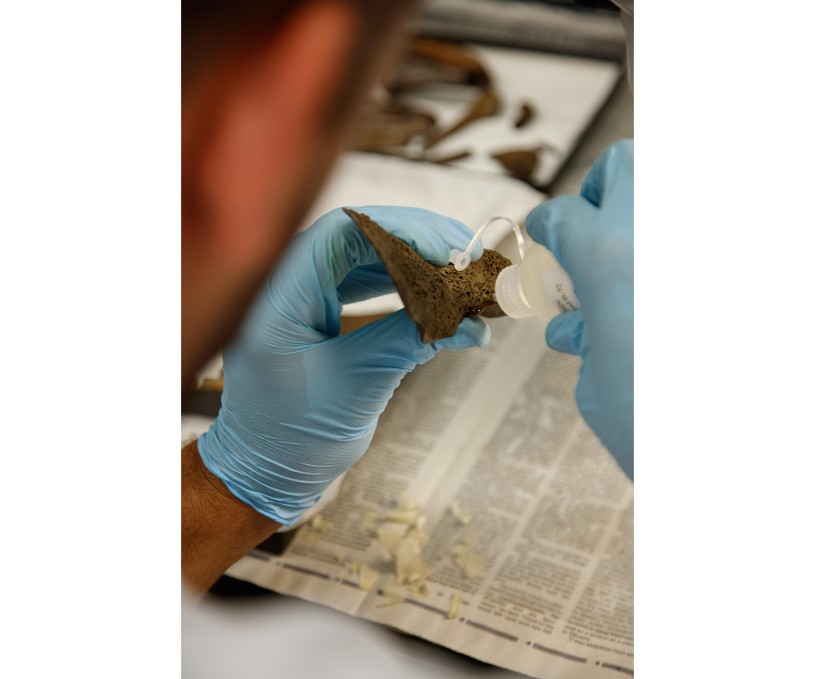

Scientists decided to take another look at the fossils in 2017. By this time, exciting technology called computed tomography (CT) scanning was a popular way to learn more about a fossil without physically cutting it open. It is the same machine used to look inside human bodies at the doctor’s office. Paleontologist Mairin Balisi thought it might be interesting to CT scan the unusual hip fossils. And it is a good thing she did! Surprisingly, the imaging showed bone spurs caused by the bones repeatedly rubbing together. This happens from chronic disease, not from an injury. Through this new information, we learned that the saber-toothed cat had a lifelong condition called hip dysplasia, a disease commonly seen in modern cats and dogs.

The Softer Side of Killer Cats

This saber-toothed cat likely walked with a limp, so hunting large prey to eat would have been difficult. Amazingly, the cat somehow survived to adulthood. Dr. Balisi and her team realized a group of other saber-toothed cats might have helped it find food and protected it from harm. By re-studying these fossils using new technology, we learned that saber-toothed cats were probably social like lions, instead of solitary like tigers.

Staff members and volunteers really sunk their teeth into their work and made these discoveries possible. From careful digging by excavators to curators identifying fossils, to researchers sharing their observations, all efforts helped piece this prehistoric puzzle together.

Through a single set of hip fossils, the world now knows the story of an extraordinary saber-toothed cat that lived thousands of years ago. What is more, we know the preferred dining style of that cat’s entire species!

You can see these unique fossils on display at the museum at La Brea Tar Pits.