Dire Wolves: Sorry, They’re Totally Still Extinct

NHM and Tar Pits experts weigh in on why dire wolves have not, in fact, been successfully cloned, and the surprising perils of de-extinction

Published April 16, 2025

By now, you’ve probably seen headlines saying that dire wolves, those extinct Pleistocene predators have successfully been cloned! That’s just not true. We spoke with the Curator of Mammalogy at NHM, Dr. Kayce Bell, and the Curator of La Brea Tar Pits, Dr. Emily Lindsey, to get the real story about what’s up with those dire wolves.

Q: So, they’ve just cloned dire wolves, right?

BELL: No, that’s not right. What we are seeing in the news right now is not a clone of a dire wolf. They’re gray wolves that scientists have genetically engineered to have physical traits in common with dire wolves, which were inferred based on genetic analyses that have not been peer-reviewed yet. So they might look somewhat like dire wolves did, but they’re genetically engineered gray wolves, full stop.

A previous, published genetic analysis found that dire wolves were a whole different genus than gray wolves, which means they’re not as closely related as say a gray wolf is to a coyote. We are still waiting for the research behind this genetic engineering to be published. Once that’s available, we can better understand the science and data behind these claims.

Q: Okay, but this means we can worry a little bit less about extinctions now that we can bring back animals?

LINDSEY: Only if your idea of conservation is a bunch of genetically engineered animals in zoos. Habitat loss is threatening animals worldwide, and cloning them (even if we actually could) is not a solution to this problem. It is worth pointing out that there is a lot of public concern just about gray wolves reoccupying their historic ranges, so the idea that we are going to start peacefully co-existing with even larger, long-extinct predators is just preposterous.

BELL: Animals don’t live in a vacuum. It is important to consider an animal’s niche and habitat. Even if we might someday be able to de-extinct an animal, we still cannot de-extinct an ecosystem. Not only are the dire wolf’s prey extinct, but we don’t have the climate of the Ice Age anymore, and anthropogenic climate change is moving us further away from those conditions every year.

“Resurrecting’ a species involves much more than having a few individuals in captivity. The usual metric is the establishments of stable, breeding populations in the wild. There is no evidence of whether Colossal’s genetically-modified wolves can breed, or what the genotype or phenotype of their offspring would be. More importantly, it's much more efficient to conserve existing species threatened by human-caused climate change, poaching, and habitat destruction than to try to bring them back after they are gone. The important thing that we’re not really talking about is how this technology could help.

Q: What do we know about dire wolves and how they went extinct?

LINDSEY: Dire wolves were slightly larger than modern gray wolves, but with more robust limbs, stronger bites, and teeth adapted for crunching bones. Scientists think they were pack hunters that chased down prey, just like modern wolves, in part because they got the same kinds of injuries! Chemical data from their bones and teeth indicate that dire wolves preyed on open-habitat grazers like horses, giant sloths, and perhaps juvenile mammoths. All of these species, and dozens more, disappeared during a massive, global wave of extinctions that dramatically altered how Earth’s ecosystems had been structured for tens of millions of years. These extinctions happened during a time of rapid climate warming and growing human populations, which probably sounds familiar because it’s analogous to the threats pushing more species toward extinction today.

Q: Were they white (like John Snow’s dire wolf from Game of Thrones)?

LINDSEY: Dire wolves were probably gray or brown, like most modern canids. It is highly improbable that they were white except perhaps in the far northern parts of their range where there was ice and snow. It just wouldn’t make sense to be snowy white in, say, Los Angeles or Peru.

Q: So they probably looked and sounded like modern wolves?

LINDSEY: One cool thing we’ve found is that they probably sounded different than modern wolves, and we know that from research on their hyoid bones. These are specialized horseshoe-shaped bones in the throat that help mammals like us and dire wolves vocalize. Researchers have found that they were significantly larger and more robust than modern wolf hyoids, and this suggests that they had deeper vocalizations than living wolves.

Q: I need to see more dire wolves. Where can I do that?

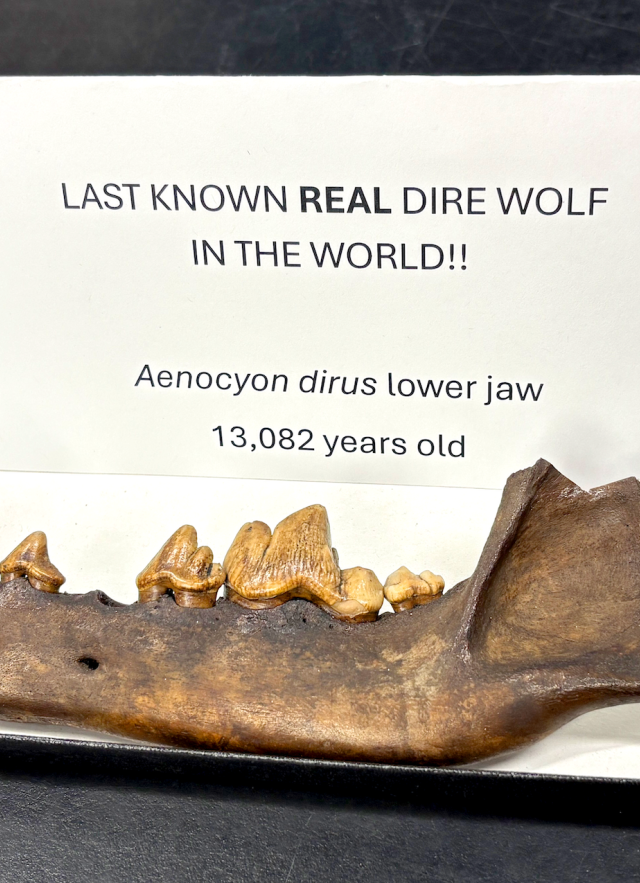

LINDSEY: More than 4,000 dire wolves have been found at La Brea Tar Pits, which is the richest Ice Age fossil site in the world. You can see hundreds of real dire wolf fossils in the museum, including “the endling”, the last known dire wolf on Earth. You might even get to see new dire wolf fossils being discovered at our excavation site!