Look, galloping down Wilshire! It’s a zebra! It’s a quagga! No, it’s Equus occidentalis, Los Angeles’s own bygone bronco.

Meet Equus occidentalis!

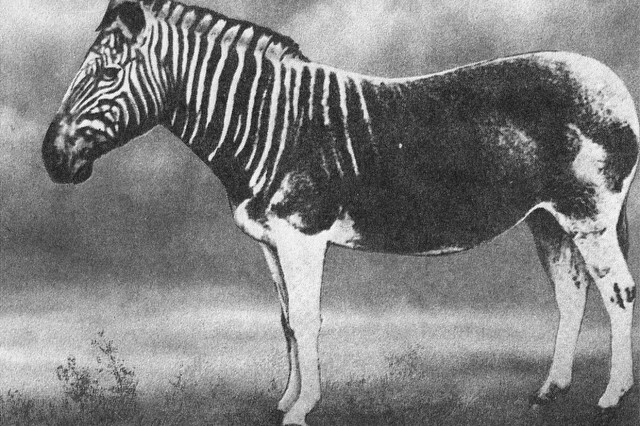

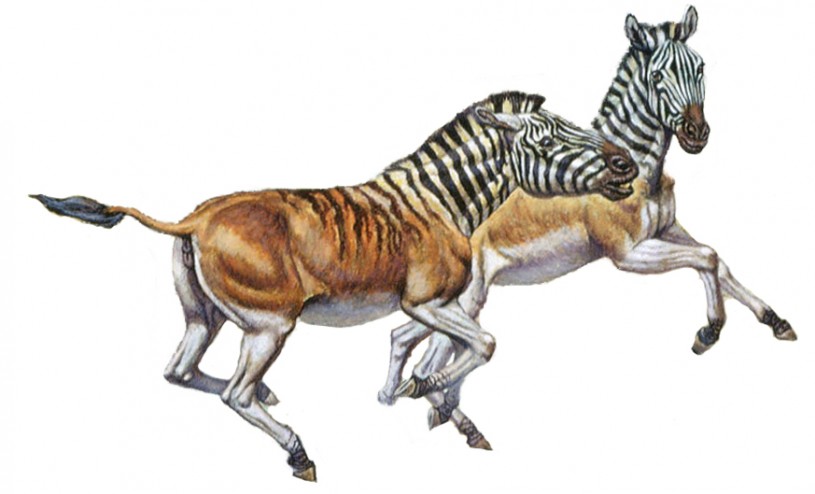

Paleontologists think E. occidentalis looked something like this zebra...

and this extinct quagga, despite not being a close relative to either

1 of 1

Paleontologists think E. occidentalis looked something like this zebra...

and this extinct quagga, despite not being a close relative to either

The Course of Horse

Whether you call them ‘horse operas’ or ‘oaters’, Westerns helped define the popular, if problematic, view of the American West, and the stars invariably rode into the sunset on the backs of horses. However, whether they were ‘wild’ horses or prized ponies, none of them were native to North America…or were they? As you probably learned in history class, conquistadors introduced horses starting with Columbus in 1493, and with the ready integration of horses into Native Americans cultures, they’d spread throughout the continent by the latter half of the 1700s. But of course, a horse found at the Tar Pits means their evolutionary history here stretches back to at least the Pleistocene (aka the Ice Age).

While the horses seen on film and the equestrian trails of Griffith Park were introduced relatively recently from Eurasia, the horse family Equidae, which includes zebras and donkeys, actually evolved in North America. The evolutionary trail to our modern horse starts small with the unassuming Eohippus almost 50 million years ago.

Known as the “dawn horse”, Eohippus reached modest heights of up to two feet. Subsisting on a diet of leaves, the dog-sized proto horse had four toes on each front foot, three on each rear foot, each toe topped off with a small hoof. It’s an illustrative base to the horse family tree, a lineage full of many branches and adaptive radiations.

The dozens of horse species in the fossil record tell a fascinating story of evolution, with adaptations keyed to surviving the grasslands of a cooler, drier planet. Faster and larger horse species thrived in the grassy plains by losing toes, gaining longer lower limbs to become faster, and evolving teeth tough enough for grass grazing.

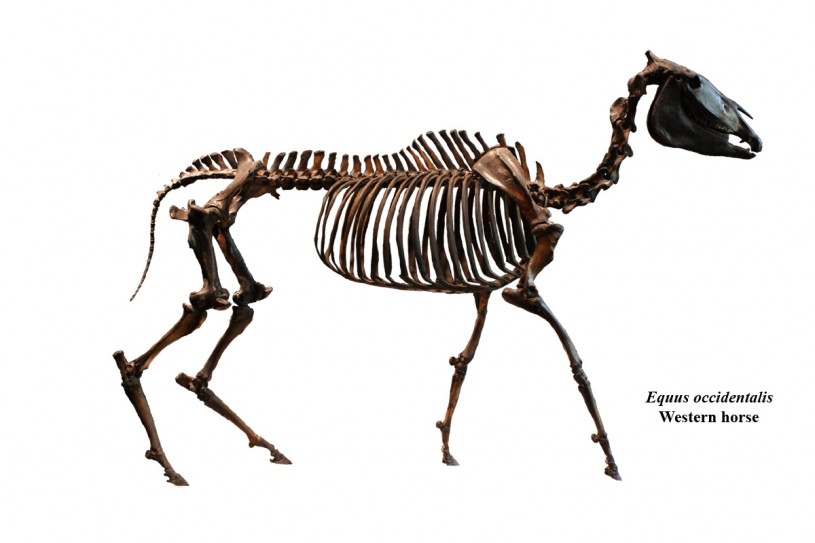

The City's Stallion

About as big as a mustang, Equus occidentalis, which means ‘Western horse’, reflects that evolution. In fact, their skeletons are so similar to modern horses, that archaeologists and paleontologists can have a difficult time telling them apart. E. occidentalis starts appearing in the fossil record around 500,000 years ago, and has been found in abundance at La Brea Tar Pits with over 200 individuals recovered. They were stout, stocky creatures, resembling modern East African zebras and the extinct South African quagga, despite not being closely related to either animal.

Recent research suggests that E. occidentalis shrank slightly near the end of the last Ice Age, and paleontologists theorize the smaller size might have reflected climate and vegetation changes. Their shift in size possibly foreshadows how modern North American ungulates (hooved animals like deer and moose) might deal with our changing climate, giving scientists valuable information in the quest to conserve our remaining megafauna.

Successfully adapting to a gradually changing climate didn’t save Western horses like E. Occidentalis from extinction. The Western horse rode into the sunset along with the other species of horse native to North America and most of the continent’s other large mammals approximately 11,700 years ago in the Late Pleistocene Extinction. Researchers at the Tar Pits and around the world are still figuring out how much climate change and the arrival of humans are responsible for these extinctions. You can see L.A.’s horse and many other Ice Age Angelenos at La Brea Tar Pits where our Pleistocene past is excavated daily.