BE ADVISED: On Sunday March 15, the parking lot at La Brea Tar Pits will be closed at 3 pm. Alternative parking structures are located at the nearby SAG-AFTRA building and the Petersen Automotive Museum. For questions or directions, please call 213.763.3466 or email info@nhm.org.

A doll meant to create a cultural bridge between two nations at a time of growing hostility

Japanese Friendship Dolls were exchanged between the United States and Japan in the 1920s as a way to connect two cultures and symbolize goodwill and diplomacy. These dolls represented a sharing of culture, history, community, and identity.

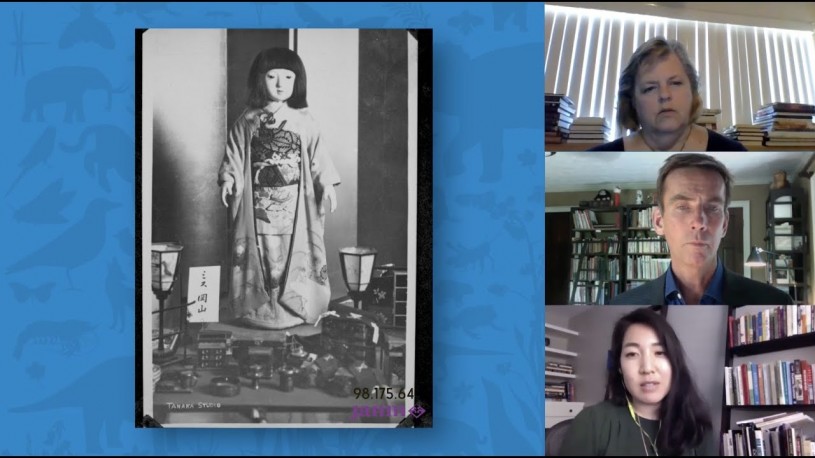

Read the story about NHM's Japanese Friendship Doll below and watch a video discussion with Kristen Hayashi, Director of Collections Management & Access and Curator at the Japanese American National Museum, Alan Scott Pate, Asian Art Expert, and Beth Werling, NHM's Collections Manager of History (Material Culture).

Kristen Hayashi is Director of Collections Management & Access and Curator at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles where she oversees the permanent collection. She is a public historian with a research interest in the history of Los Angeles’s diverse communities. Previously, she worked at the Natural History Museum for a number of years in a variety of capacities, including as part of the core content team for the “Becoming Los Angeles” exhibition.

Alan Scott Pate received his M.A. from Harvard and found his niche in the world of Asian art in 1993. He narrowed his primary focus to Japanese dolls and began to research, write, and lecture on this topic. Alan has written three books on the history of Japanese dolls and guest-curated a number of exhibitions in the U.S., Japan, and Poland and along the way has become a preeminent dealer though his company, Alan Scott Pate: Antique Japanese Dolls based in Acworth, Georgia. In 2016, Alan published his comprehensive work on this subject: Art as Ambassador: The Japanese Friendship Dolls of 1927.

Beth Werling holds a B.A. in History from Stanford, an M.A. in History from New York University, and post-graduate work in Museum Studies. As Collections Manager for the History Department’s Material Culture, she has overall responsibility for its wide range of three-dimensional artifacts and the collections at the William S. Hart Museum. Beth is Vice President of Hollywood Heritage, serves on the advisory board of the Historical Committee of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ - Science & Technology Council and the Art Director’s Guild archives, and co-curated an exhibition at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences.

A Story of 58 Silent Envoys

On November 27, 1927, a ship from Japan arrived in the Port of San Francisco. Onboard was a contingent of fifty-eight envoys whose sole mission was to convey messages of friendship to American children.

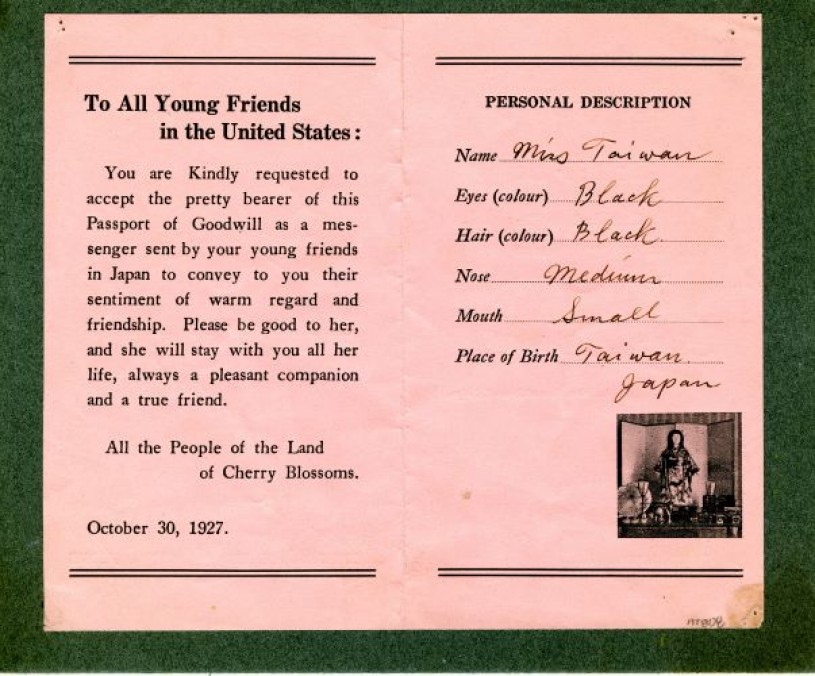

They received a mixed reception in California, from passive-aggressive newspaper headlines proclaiming a “Japanese Invasion” to crowds of Japanese Americans swarming over walls to glimpse these foreign diplomats who never spoke a word; they were dolls. One of those passengers, “Miss Taiwan,” resides today at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

“Miss Taiwan,” standing at nearly three feet tall, is one of the Japanese Friendship Dolls, which is how they are known collectively. These dolls were never intended to be played with, instead, they were meant to serve as diplomats to create a cultural bridge between two nations at a time of growing hostility.

In the 1920s Reverend Sydney Gulick who had been a missionary in Japan for twenty-five years was alarmed by the escalating rhetoric between the U.S. and Japan. After the passing of the Immigration Act of 1924, which banned all Japanese from entering the U.S., Gulick took action. Believing that “we who desire peace must write it in the hearts of children,” he proposed that children throughout the U.S. collect money to purchase dolls to send to the children of Japan as a gesture of friendship and to encourage cultural understanding. Through his connections with religious organizations, Gulick formed the Committee on World Friendship Among Children.

American schoolchildren purchased inexpensive manufactured dolls at local stores. Some dolls wore their store-bought clothing while others had homemade clothes made by the children—or more likely their mothers. What the dolls had in common were their looks; the vast majority were blonde, blue-eyed dolls.

These “Ambassador Dolls” were sent to Japan with handwritten letters from the children describing their life in America and expressing their desire for friendship to their Japanese counterparts. The dolls arrived in Japan in time for the hina matsuri, the nation’s most important Girl’s Day Festival. Unlike Americans who regard dolls as toys, the Japanese feel that dolls are individuals; each with its own personality or spirit. The “blue-eyed dolls” as the Japanese nicknamed them arrived in time for the March 1927 hina matsuri to an enthusiastic welcome. The Emperor of Japan even granted an audience to a group of dolls.

Although Gulick and his Committee stressed that the Japanese should not reciprocate the American gift, the country felt honor bound to do so. Rather than purchasing dolls, however, the Japanese created fifty-eight individually designed and created dolls to send to the United States. Each was named after a different city, region, prefecture, or colony of Japan. They were rushed into production so that they could arrive in the U.S. in time for Christmas.

Fifty-one of the fifty-eight Japanese Friendship Dolls, including “Miss Taiwan,” were made by the Yoshitoku Doll Company in Tokyo. These dolls are a little under 33 inches in height with human hair and glass eyes. Each has a squeaking mechanism in its chest. When the ribs are depressed it sounds as if the doll is crying “mama”. The Yoshitoku dolls’ torso is a wooden core covered with fabric, and their legs are hinged to allow the doll to sit.

On the back of each doll under the kimono is a label in English reading “The Tokyo Doll Wholesale Traders Association” with the name of the artist responsible for that specific doll. The label on “Miss Taiwan’s” back identifies Takizawa Koryusai as her artist. He would have been responsible for creating the head, hands, and feet while the remainder of the doll would have been produced at the Yoshitoku factory. This process explains why each Japanese Friendship doll has its own unique facial features; they were individually sculpted using lightly pigmented pulverized oyster shells, known as gofun.

Each doll had its own silk kimono with an individual “family crest” and was dressed by the official dresser for the ladies of the Japanese Imperial Court. They were accompanied by a “bridal” trousseau consisting of chests, makeup stands, mirrors, folding screens, lanterns, tea sets, sewing kits, parasols, sandals, and small purses. Today the Japanese Friendship Dolls are recognized as among the most significant dolls ever produced by Japan.

When the dolls arrived in San Francisco, Gulick and the Committee on World Friendship Among Children quickly organized a reception for the Japanese Friendship Dolls which was followed by a nationwide tour. The goal was for as many Americans as possible to view the dolls and to learn about Japanese culture; knowledge would foster understanding in the children for different cultures.

After several appearances on the West Coast, the dolls traveled to Washington, D.C., and then to New York City for further arrival receptions. The dolls were then separated into smaller groups to tour throughout the country, usually appearing at schools, churches, and libraries. They were frequently hosted by the same community organizations which had been responsible for sending the blue-eyed dolls to Japan the previous year.

One of the major venues was the World Sunday School Convention held at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles in July 1928. Afterward, the Japanese Friendship Dolls exhibited at the event remained in Los Angeles until the Committee found homes for them. The Committee’s plan from the beginning had been to place the dolls in permanent sites, preferably where they could continue to be viewed and appreciated by children. A number of libraries and museums throughout the United States were gifted with a doll.

The Los Angeles Museum of History, Art, and Science (now the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County) was gifted with one of the dolls following the World Sunday School Convention. The Museum’s doll was known as “Miss Taiwan” for decades based on the brass nametag on her stand. Recent detective work by Japanese doll scholar Alan Scott Pate, however, revealed that “Miss Taiwan,” despite her nameplate, is actually “Miss Hyogo”. In the haste of packing and unpacking the Japanese Friendship Dolls during their tour in 1928-29, the dolls were mixed up and not always re-matched with their proper stands.

Fortunately, because each doll had a unique crest on its kimono they could be properly identified by matching them to photographs taken on their original stands prior to their tour. Today, only five are still united with their original stand and nameplate.

But more importantly, what of their message of peace?

It is tragic to realize that many of the Japanese and American children that exchanged letters and life stories in 1927 were at war with each other fourteen years later. Although World War II appeared to denote a failed mission, in recent years there has been a renaissance.

When Japan suffered a 9.0 earthquake followed by a tsunami in 2011, the Milwaukee Public Museum in Wisconsin placed their Japanese Friendship Doll on display in a symbol of friendship and compassion for the Japanese people. Thus the Japanese Friendship Dolls continue to fulfill their mission nearly a century later.

In the spirit of the Japanese Friendship Dolls, we invite you to make your very own doll and “send” it to a friend via social media. Visit the Friendship Doll Art Exchange activity page.