Picture yourself walking down Wilshire Boulevard on your way to La Brea Tar Pits (you found a good parking space, despite whatever's backing up traffic), when a pair of ears come into view behind one of the food trucks. The ears, sort of like a horse's, recede only to be replaced by a long snout ending in prominent lips, which promptly hawk a gob of spit in your direction. You pass the food truck to find a giant North American camel.

Meet Camelops hesternus

Way More American Than Apple Pie

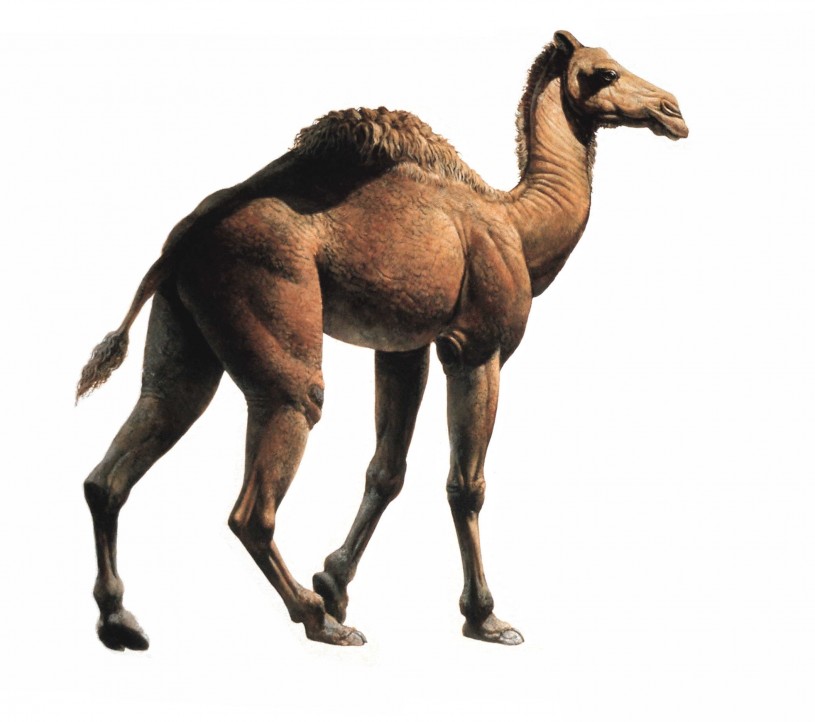

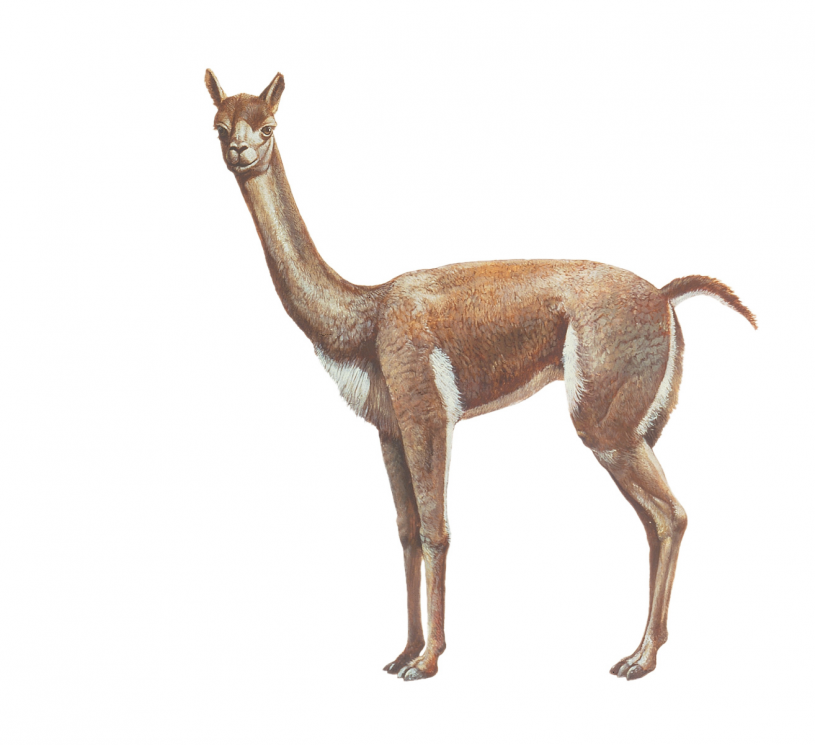

Camelops hesternus, which translates to "camel-face of yesterday", or the more poetic "yesterday's camel", was a West Coast native that ranged as far as modern Alaska, Mexico and into the Midwest. What's more, the fossil record reveals that the Camelidae family, the group that includes modern single-humped dromedary and double-humped Bactrian camels found in Asia and Africa, as well as the llamas and vicuñas of South America, got its start in North America. The ancestors of modern camels crossed into Asia via the Bering Isthmus some 7 million years ago, and through the Isthmus of Panama into South America around 3 million years ago.

One Hump or Two?

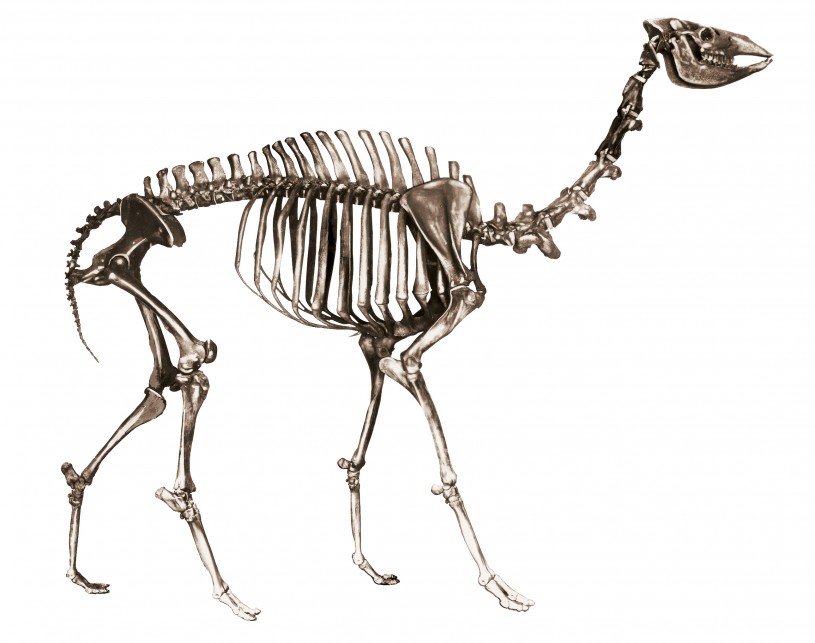

The ancient camels found at La Brea Tar Pits were a foot taller than modern dromedary camels, measuring around 7 feet from the shoulder, and had longer necks. Their long legs suggest they were capable of running 40 mph, around the same speed as modern camels. By studying marks on their teeth, paleontologists have determined that Camelops would have been a browser, feasting on shoots, leaves and other plants in reach. With an extra long neck, it's easy to imagine that a lot of vegetation was in reach. It's unclear whether or not Camelops shared the characteristic hump (or humps) of modern dromedary and Bactrian camels. Soft tissue is not preserved well in the fossil record, and the animal's vertebrae show no signs of supporting a fatty hump.

Of course, if you think you're seeing a Camelops hesternus walking down Wilshire, it's probably an escaped Camelus (modern camel or dromedary) from the L.A. Zoo. Like many of the megafauna that lived alongside it, Camelops went extinct around 10,000 years ago. While these disappearances coincide both with end-Ice Age climate changes and the arrival of humans in North America, researchers have not made a definitive determination on the cause of the extinctions.

You can still see them on display at La Brea Tar Pits. Remains of over 40 Camelops have been excavated from La Brea Tar Pits, where excavations have been ongoing for more than 100 years. Paleontologists are constantly making new discoveries at this iconic site, and researchers continue to study the fossils of giants like Camelops to better understand their extinction and threats to modern animals like climate change.