Meet Teratorn, the Largest Bird Found at La Brea Tar Pits

The teratorn was undoubtedly big, but was it a big vulture or something else?

Published April 4, 2025

A shadow passes over you, and for a second, you wonder, ‘Is that a plane?’ But this is Pleistocene Los Angeles, and the biggest thing in the sky is the teratorn, a name that translates to "wonder bird". Look closer. Is its head pink? We're still wondering.

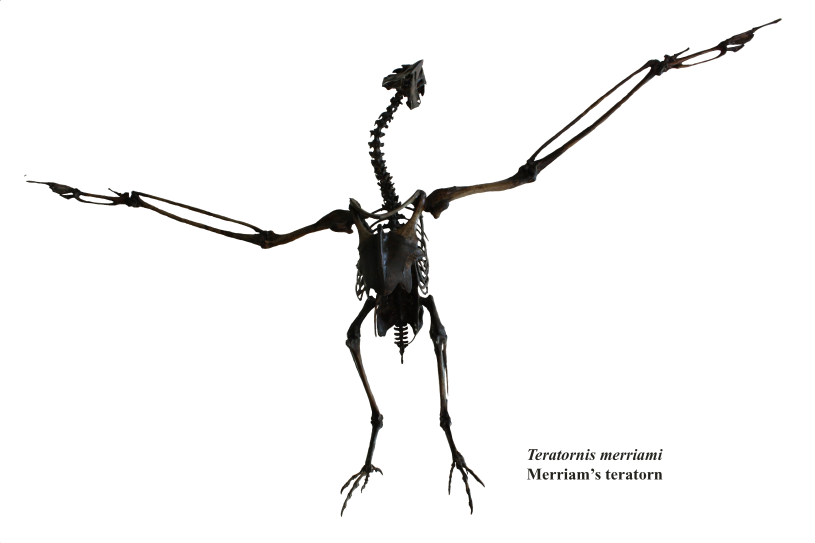

Meet Teratornis merriami.

Were these big birds bald or what???

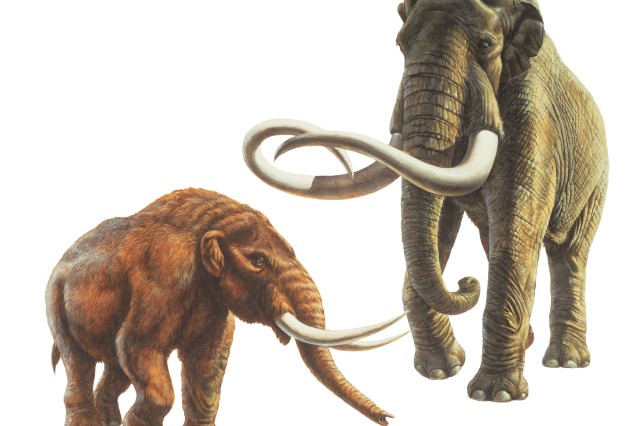

In a world of mammoths and mastodons on land, Merriam’s teratorn (Teratornis merriami or just teratorn) was a giant of the sky, about a third larger than the California condor—the biggest modern bird in the region. Teratorn boasted a wingspan of up to 12 feet and a vicious hooked beak on top of a condor-like body. For a long time after its description in 1909, paleontologists and the paleoartists who brought these gigantic birds back to life pictured the teratorn as something like a giant vulture, but subsequent researchers at La Brea Tar Pits end elsewhere have painted a different picture of the most famous bird from the Tar Pits.

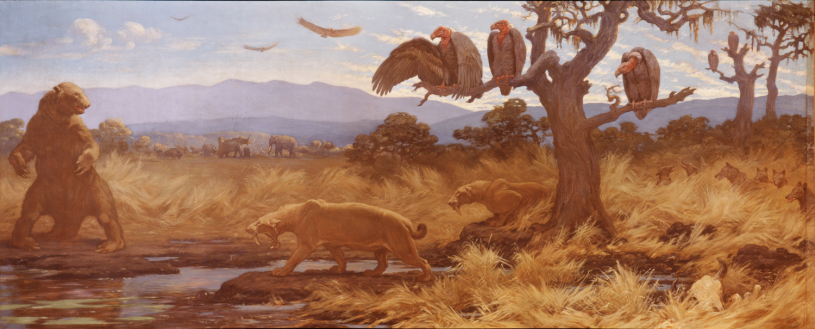

Famed paleoartist Charles Knight depicted teratorns as dark-feathered, bald-headed scavengers in the vein of turkey vultures and California condors, whose bare skulls help them stay clean while digging into decomposing feasts.

Their relatively stout, short legs and talons meant that teratorns couldn’t snatch prey in mid-air but could brace themselves against a big dead animal (or sticky asphalt) to rip off chunks of meat. With their impressive wing spans—perfect for soaring—and their hooked beaks—perfect for ripping chunks of flesh off large dead animals—it’s easy to imagine teratorns living that vulture lifestyle: catching the whiff of decay on the breeze and then landing in the asphalt to tear into a tasty rotting bison only to find themselves stuck.

Whether they boasted impressive plumage or cue balls is lost to the goopy asphalt of time, but later research muddied the picture of the teratorn as a giant vulture.

Venturing Beyond Vultures

The Tar Pits' first official Curator of Ornithology, Dr. Ken Campbell, challenged the idea of teratorns as Ice Age vultures in two papers from the 1980s. With detailed inspection of the extinct birds’ anatomy—especially their skulls—Campbell and his coauthors argued that while their hooked beaks looked like scavengers, and their bodies resembled condors, the giant birds’ skulls told a different story.

The researchers found that their skulls weren’t quite right for ripping chunks of flesh off the dead bodies of megafauna like camels or mastodons. Vultures use their beaks as meat hooks to pull beakfuls of meat from carcasses, but teratorns' broader and more flexible skulls suggested that teratorns would have been able to open their mouths wide enough to swallow much smaller mini fauna like frogs and rodents to things as big as hares, which are basically the size range of newborn babies.

They imagined their active hunter as having a secretary bird’s white body and gray wings to best camouflage themselves, scouring the landscape for small animals in the air and on foot. The fossil bird with the closest hunting style found at the Tar Pits would be the crested caracara, a long-legged, bald-faced but impressively quaffed falcon that can still be found in the region and at lower latitudes all the way to South America. Other researchers found that teratorns are just as closely related to storks as they are to vultures and suggested that teratorns’ hooked beaks and the ability to swallow newborn baby-sized creatures whole pointed to a diet focused on fish.

Truth in Teratorn Bones

A later study from 2006 looked at the diet of extinct presumed scavenger birds like the black vulture and teratorn but looked inside their bones for answers. What we eat—and the diets of extinct animals like teratorns—are recorded in our skeletons through traces of oxygen, strontium, nitrogen, and carbon. The levels of these stable isotopes in bone or teeth can correspond to particular diets. When researchers in the 2006 study looked at stable isotopes in teratorns’ bones, they found that the large birds were eating grazing and browsing animals mammals like bison and camels. They noted that while they couldn’t settle the debate about whether teratorns were scavengers or hunters, they could rule out a fish-heavy diet.

So were teratorns big vultures? Like so many other extinct large animals found at the Tar Pits, they were more than just a bigger version of living creatures, and continued research has both sharpened the picture and raised more questions about how these animals lived. Most of the research on teratorns and the rest of the birds from La Brea Tar Pits was done decades ago, and newer studies could upend reframe teratorns once again. No doubt, new scientific discoveries and advances in research techniques will further expand the bounds of our imagination when it comes to this iconic Tar Pits bird.

The team behind the Tar AR reconstruction above aimed for something in between, keeping Campbell’s colorway but leaving a narrow neck in case new evidence points more convincingly to a balder bird. Want to bring the big bird home with you? Scan the QR code at the bottom of this page.