Solving a Juniper Seed Mystery at La Brea Tar Pits

How identifying a mysterious fossil seed reveals Ice Age climate change

Published January 15, 2025

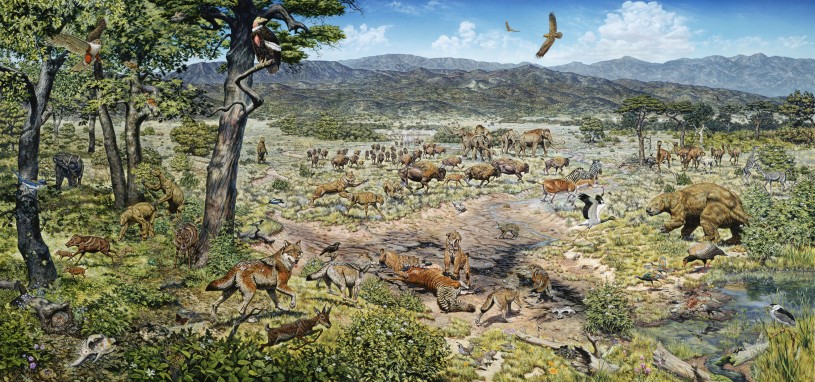

The Root of Understanding Ice Age Climate

Between giant sloths, dire wolves, and mastodons, L.A.’s Ice Age past can feel distant and strange, but from the planet’s perspective, the world of those Ice Age giants was practically yesterday, and the incredible changes in climate and biodiversity have lessons to teach us as we face the human-caused climate change and biodiversity crises happening right now. Having the clearest picture possible of life then can help us conserve nature in the present and future. To see that, you have to look past the weird and wonderful extinct animals and focus on the plants.

“If you're looking at terrestrial life, most everything starts with plants. They are the organisms that capture the sun’s energy and make it available to all animal life. In addition, they form the habitat for all terrestrial ecosystems. So if you don't understand what's going on with the plants, you're missing the initial puzzle piece for that whole larger picture,” says Dr. Jessie George, postdoctoral researcher at La Brea Tar Pits. Luckily for us, plant parts got stuck in the asphalt and fossilized with all those Ice Age animals.

A Seedy Pleistocene Mystery

The mammoths and saber-toothed cats that shape our imagination of Ice Age Los Angeles browsed, grazed, and hunted in juniper woodlands. More than just a source of food for giant herbivores, junipers were keystone trees and shrubs in the region, in turn shaping the landscape for at least 47,000 years before completely vanishing from the region in the same extinction event that erased most of the megafauna.

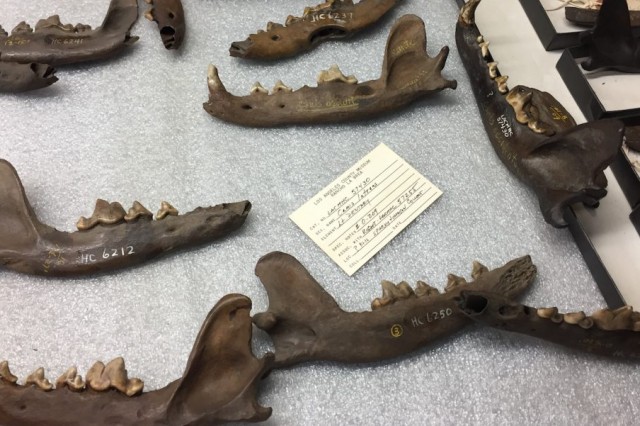

Along with fellow paleobotanist Dr. Regan Dunn and other Tar Pits Researchers, George has been piecing together the larger picture by exploring the fossilized branches, seeds, wood, and leaves that make up the botany collection. Sifting through the collection George led a study published in the journal New Phytologist.

Researchers have long known that there are two different species of juniper found at the Tar Pits—the large-seeded J. californica (California juniper), and the small-seeded, mystery juniper. With distinct tolerances for temperature and drought, fossil junipers play a crucial role in understanding the changing climate of the last Ice Age, and how junipers can survive our climate future, but the identity of the mystery seed remained uncertain—until now.

“We set out to identify this mystery juniper, and in the process, we found a number of exciting things,” says George. “Number one, we identified this juniper as Rocky Mountain juniper, and it is one of the most extreme examples of a plant going extinct locally at La Brea. It’s not present anywhere in California today.”

As part of the study, George and the other Tar Pits researchers radiocarbon dated hundreds of seeds of the two species of juniper, which led to the second exciting finding: “In the process of radiocarbon dating these juniper species, we found this really interesting pattern of reciprocal presence—either California juniper only or Rocky Mountain juniper only.”

Because each plant survives in specific conditions, its presence helps understand what the climate was doing. George and her colleagues found that this dance between the two junipers matched up with long periods of drought and warm, dry weather that would otherwise be hidden in the fossil record.

“California juniper is a much more drought tolerant species. It withstands moisture deficit way better than Rocky Mountain juniper,” says George. “Through these back-and-forth occurrences of the two species from the Tar Pits, we have this really fascinating record of aridity and drought that was previously undetected.”

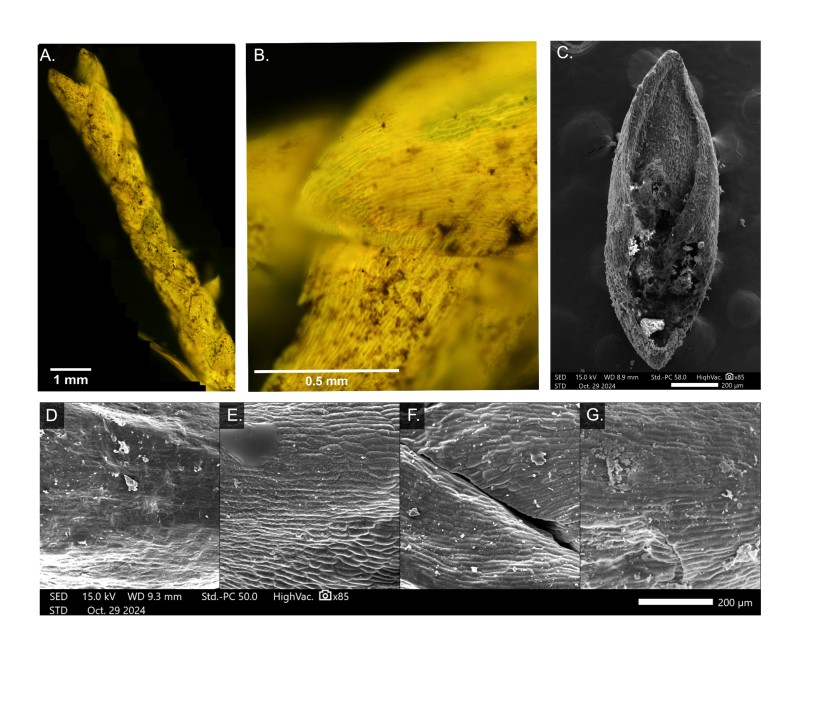

The unknown juniper seed is tiny, about as big as Lincoln’s forehead on a penny, and its small size made it more difficult to study, especially since DNA has yet to be extracted from Tar Pits fossils. Without DNA, George compared the structure of seeds and branchlets (the scaly leaves) to other juniper species—the only way to uncover its identity. It required careful comparison using advanced microscopy, image analysis, and species distribution modeling (SDM) until the team reached a definitive answer.

While climate definitely played an important role in their local extinction, the team thinks that the abrupt disappearance of Ice Age megafauna and fires started by humans may have also contributed, much like in the case of those iconic giant mammals. In a hotter, drier climate, even plants well-adapted to drought couldn’t survive the extra stress of human fires. This is especially true for plants that are not adapted to wildfire. Unlike many other conifer species, juniper doesn’t survive or re-grow following fires very well. The finding highlights the threat junipers continue to face from human-caused climate change and could help inform conservation efforts going forward.

“We're seeing events of really dramatic decline of these trees in the southwest today because of warming temperatures and increased wildfire caused by modern climate change. So a direct record of how this might have occurred in the past, what factors were at play, and where those boundaries occurred is incredibly important,” says George.

“It gives us a better framework to understand a baseline of climate and environment to contextualize changes in other plant life and the fauna that we see during these periods of significant change in the past. As our ability to precisely date fossils improves, better and more detailed information is revealed from ancient life at La Brea.”

George and her colleagues will keep digging through the fossil plants at La Brea Tar Pits for more pieces of the Ice Age puzzle.