Year of the Rabbit

Celebrate the 2023 Lunar New Year with highlights from the collection

We are devastated by the tragic events that took place in Monterey Park and offer our condolences to victims and families of this senseless crime. NHMLAC stands behind the Los Angeles AAPI community, including our visitors, members and staff. Our hearts are with each of you on this bittersweet time of celebration.

The Lunar New Year 2023 ushers in the Year of the Rabbit, which is celebrated in many Asian countries such as China, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia. In the story of the Jade Emperor’s race, the rabbit used its quick, quiet, and skillful nature to come in fourth place. It was doing well in the race as it jumped from stone to stone, but slipped suddenly and recovered by grabbing onto a log that floated across the finish line ahead of the dragon.

Animal associations in the zodiac can vary per country, and in Vietnam, 2023 is celebrated as the Year of the Cat. There are a few scholarly explanations for this difference; one explanation is that the cat was disqualified from the Jade Emperor's race because it arrived last after being pushed by the rat into the water. In the Vietnamese version of this story, there is no rabbit in the race, and the cat swims across the finish line, arriving in fourth place.

To celebrate the Lunar New Year, we invite you to learn about the natural history of the elegant, alert, and patient rabbit and explore highlights from the Museum collection connected to the rabbit—both the rabbit itself and “rabbit” fish, birds, snakes, and more!

The Natural History of the Rabbit

Rabbits belong to the mammalian order Lagomorpha and evolved roughly 40 million years ago during the late Eocene. There are 104 different species of lagomorphs, which include pikas, rabbits, and hares. The fossil record indicates that the order was much more diverse in the past, with over 230 species. Lagomorphs are found around the world, with pikas being native to North America and Asia, hares native to Europe, Asia, Africa, and North America, and rabbits native to Europe, parts of Africa, Central and Southern Asia, North America, and of South America; although they have been introduced to other parts of the world, most famously in Australia.

Pikas are quite different in appearance from rabbits and hares; they are much smaller and have relatively smaller ears and hind feet, and no external tail. Rabbits and hares have elongated ears and hind feet and short furry tails. The large ears of some hare species, like the desert-dwelling Black-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus californicus), function as highly vascularized radiators, allowing them to dump excess body heat or conserve heat by regulating circulation. Although the common names of this group can be confusing (e.g., Lepus californicus is the Black-tailed jackrabbit even though it is a hare), the differences between rabbits and hares are primarily based on evolutionary relationships. Other differences are that hares make a nest—called a form—on the ground among vegetation, tend to be solitary, and are born fully furred and active. On the other hand, rabbits generally live and breed in burrows, are often colonial and are born less developed than hares, requiring more parental care. Although some rabbits, such as cottontails and hispid hares (which are really rabbits), are solitary and have forms.

Rabbits were bred and kept in captivity for food and fur as early as the Roman Period, with domestication considered complete by roughly 1500 CE. These rabbits were domesticated from European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) and have been kept as pets since the 19th Century. Domesticated rabbits are also bred and kept as livestock, with the largest per capita consumption (up to 19 pounds a year) in some European countries.

NHM’s Mammalogy research collection has approximately 700 lagomorph specimens from 15 countries and 25 states in the U.S.! The collection helps us understand and document historical and modern patterns of biodiversity, and are actively used for research by NHM scientists and researchers worldwide.

A virtual rabbit and “rabbit” tour through the Museum collections:

Cottontails, past and present

Known as the Desert cottontail rabbit, Sylvilagus audubonii is widespread in Western North America and are often called bunnies. Cottontails are active during the day, and the young, called kits, are prey for nearly every local carnivore; therefore, cottontails have a high reproductive rate. Cottontails have multiple litters a year; those kits that survive to adulthood grow quickly and are full-sized by the time they are three months old.

The next time you visit the La Brea Tar Pits, you might see someone working on Box 14 of the Project 23 excavations. Originally over 86,000 pounds (39,000 kg) of asphaltic sands, silts, clays, and fossils, the staff and volunteers are now down to the last ~thousandth of that material. Within Box 14, bones of the Desert cottontail are some of the most common fossils found. These rabbits are the same species that are still found living in the surrounding park today.

This approximately 37,000-year-old right dentary (lower jaw) from The La Brea Tar Pits belongs to the Desert cottontail. In Fox et al 2019, 52 out of 59 identified specimens in a sample of leporids (rabbits and hares) from across multiple Project 23 deposits belonged to this species. This suggests that the area likely had a more open environment, with coastal chaparral, sagebrush, and juniper-based vegetation rather than dense brush, from ~45,000 - 37,000 years ago. Although we find our rabbits as fossils alongside our extinct species, those that are still alive today can give us more detailed information about what it was like in a particular place, at a particular time.

The jackrabbit that is actually a hare

Milena Acosta

A Black-tailed jackrabbit, Lepus californicus, from the Museum's Mammalogy Collection.

Milena Acosta

This taxidermy Black-tailed jackrabbit, Lepus californicus, can be seen in the Museum's Nature Lab.

Milena Acosta

The Blacktailed jackrabbit, Lepus californicus, skeleton.

1 of 1

A Black-tailed jackrabbit, Lepus californicus, from the Museum's Mammalogy Collection.

Milena Acosta

This taxidermy Black-tailed jackrabbit, Lepus californicus, can be seen in the Museum's Nature Lab.

Milena Acosta

The Blacktailed jackrabbit, Lepus californicus, skeleton.

Milena Acosta

The Black-tailed jackrabbit, Lepus californicus, is the most common hare in Western North America, ranging from Mexico to Canada, common in California, and living from sea level to high elevations (over 10,000 ft). These are one of the largest North American hares at around two feet tall and weighing up to six pounds. Like all hares, they are very fast runners (reaching over 50 mph for short distances), can jump up to 10 feet, and have large, wide ears to release body heat.

Within the Project 23 excavations at La Brea Tar Pits, the Black-tailed jackrabbit is found less commonly than the cottontail rabbits. Pictured above are calcaneii (heel bones) from a single day’s excavating, with the top seven belonging to a jackrabbit and the bottom one belonging to a cottontail. This photo shows one of the easiest ways that the excavation team can quickly tell the difference— their feet are a hare larger.

Fossil Relatives

Palaeolagus haydeni is an extinct lagomorph living in western North America about 30 million years ago. Palaeolagus is probably ancestral to both living rabbits and hares! You can view this specimen at NHM in the Cenozoic Mammal Hall.

A bird named Rabbit, Rabbit

Milena Acosta

Willow Ptarmigans, Lagopus lagopus, vary in color depending on the season. They are snowy white in winter and an intricate mix of reds and browns in summer.

Milena Acosta

Ptarmigans are well suited to brutally cold winters, using heavily feathered feet to walk across fresh snow.

Milena Acosta

The Willow Ptarmigan got its scientific name due to the feather-covered feet that looks like a rabbit’s foot.

1 of 1

Willow Ptarmigans, Lagopus lagopus, vary in color depending on the season. They are snowy white in winter and an intricate mix of reds and browns in summer.

Milena Acosta

Ptarmigans are well suited to brutally cold winters, using heavily feathered feet to walk across fresh snow.

Milena Acosta

The Willow Ptarmigan got its scientific name due to the feather-covered feet that looks like a rabbit’s foot.

Milena Acosta

The Willow Ptarmigan has the scientific name Lagopus lagopus, meaning rabbit foot (twice). A type of grouse in the pheasant family found in tundra habitat, the Willow Ptarmigan got its scientific name due to the feather-covered feet that look like rabbits’ feet. These feathers increase the surface area of the feet, effectively serving as snowshoes and helping them walk across fresh snow. In addition, they molt their body feathers twice a year, from mottled brown in the summer to snowy white in the winter to stay camouflaged year-round.

hind feet as big as Snowshoes

Milena Acosta

Snowshoe hare, Lepus americanus, from the Museum's Mammalogy Collection.

Milena Acosta

A close up look at the Snowshoe hares big, furry hind-feet.

1 of 1

Snowshoe hare, Lepus americanus, from the Museum's Mammalogy Collection.

Milena Acosta

A close up look at the Snowshoe hares big, furry hind-feet.

Milena Acosta

Snowshoe hares, Lepus americanus, are native to North America and get their common name from having big, furry hind feet that act like snowshoes, preventing them from sinking into the snow when they hop. Snowshoe hares are noted for their winter and summer changes in fur color—white in winter and brownish-red in summer—for adaptive camouflage to the surrounding environment. However, climate change is shifting the timing and density of snowpack so that hare camouflage is sometimes out of sync resulting in high predation rates.

Hares from the Sea

Milena Acosta

California sea hares, Aplysia californica, are housed in both the Malacology Collection and in the Marine Biodiversity Center at NHM.

Cricket Raspet, iNaturalist

California sea hares are reddish-brown to greenish-brown, but the color can vary based on the type of algae it eats.

1 of 1

California sea hares, Aplysia californica, are housed in both the Malacology Collection and in the Marine Biodiversity Center at NHM.

Milena Acosta

California sea hares are reddish-brown to greenish-brown, but the color can vary based on the type of algae it eats.

Cricket Raspet, iNaturalist

The California sea hare, Aplysia californica, gets its name from the two long rhinophores that project upward on their head and resemble the ears of a hare. The word ”rhino” means nose, and “phore” means carrier, and these structures allow the sea hares to pick up chemical cues in the water—primarily from other sea hares during mating season.

A Snake Named Rabbit

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Living Collections

Rabbit, the Colombian red-tail boa (Boa constrictor contsrictor), is cared for by the Museum's Living Collections staff.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Living Collections

Rabbit lives behind the scenes but he often guest stars at our special events like Haunted Museum, Dino Fest and our daily 3pm Animal presentations.

1 of 1

Rabbit, the Colombian red-tail boa (Boa constrictor contsrictor), is cared for by the Museum's Living Collections staff.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Living Collections

Rabbit lives behind the scenes but he often guest stars at our special events like Haunted Museum, Dino Fest and our daily 3pm Animal presentations.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Living Collections

He may not be covered in hair, but he’s still a rabbit to us! Meet Rabbit, our resident Columbian red-tailed boa, who joined our Museum family in 2016. We often are asked where Rabbit got his name, and the story behind it may surprise you. Before joining us, Rabbit’s previous owner noticed he took a liking to another one of her snakes, “Ixchel,” named after the Mayan moon goddess. The goddess Ixchel is often depicted with a rabbit as her companion. Since Rabbit became a regular companion to Ixchel, the snake, the name seemed fitting, and he’s been “Rabbit” ever since!

Quetzalcoatl and the Rabbit

Dan Watson

Dan Watson

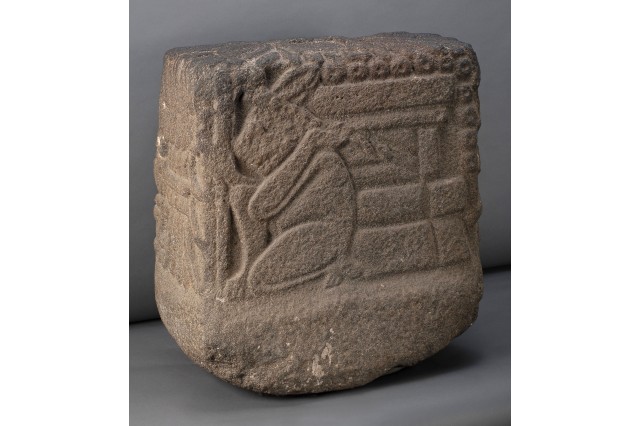

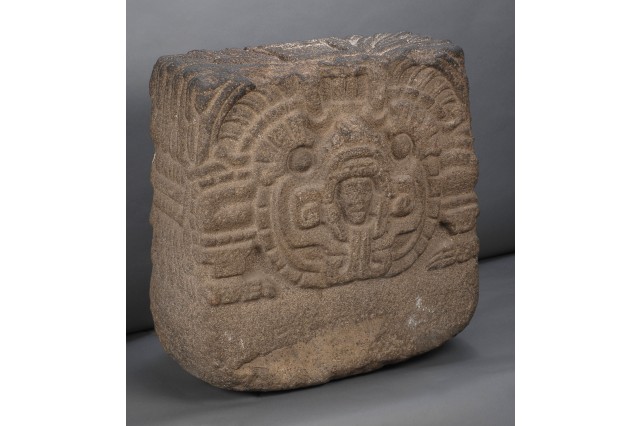

The front side of the large architectural element likely representing the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl.

1 of 1

Dan Watson

The front side of the large architectural element likely representing the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl.

Dan Watson

This large stone architectural element is displayed at NHM inside the Visible Vault exhibition. As it is displayed, the image on the side facing the viewer represents the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl with the Morning Star emerging from its jaws, an image associated with Aztec and Toltec cultures. A mirror in the display reflects the carving on the other side depicting a rabbit carrying a house on its back. This carving may be a central Mexican interpretation of a Maya symbol for the transition from one year to the next.

There’s A "rabbit" on an “acorn” attached to a whale in the water at the bottom of the sea

Milena Acosta

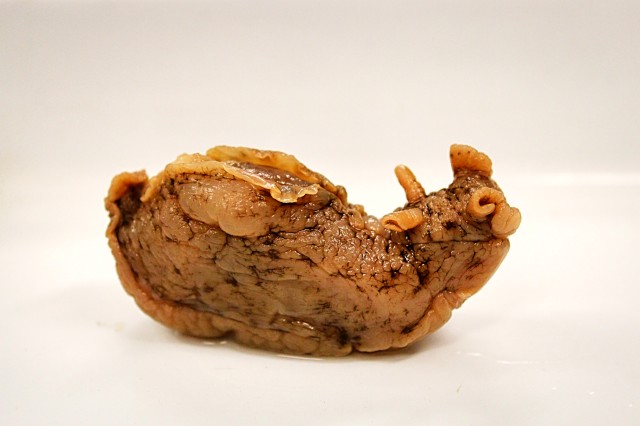

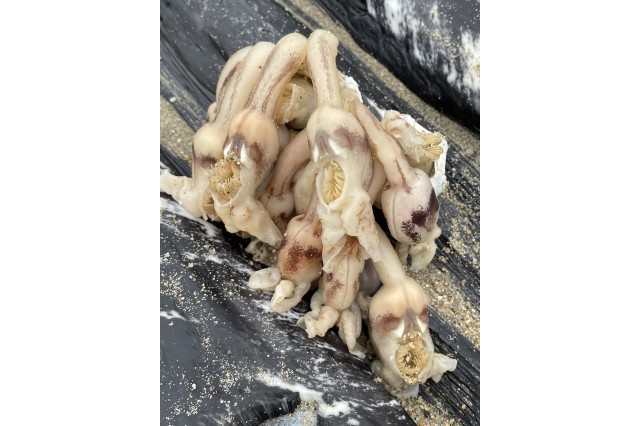

Rabbit-ear barnacles, Conchoderma auritum, housed in ethanol for long-term preservation from the Museum's Crustacea Collection.

Milena Acosta

This specimen was attached to an acorn barnacle which was attached to a humpback whale!

Cricket Raspet, iNaturalist

In this photo, we can see a living Rabbit-eared barnacle attached to a whale.

1 of 1

Rabbit-ear barnacles, Conchoderma auritum, housed in ethanol for long-term preservation from the Museum's Crustacea Collection.

Milena Acosta

This specimen was attached to an acorn barnacle which was attached to a humpback whale!

Milena Acosta

In this photo, we can see a living Rabbit-eared barnacle attached to a whale.

Cricket Raspet, iNaturalist

These alien-looking Rabbit-ear barnacles, Conchoderma auritum, are somewhat counterintuitively crustaceans and not mollusks! These soft-bodied crustaceans are most often found living commensally on the skin of whales. This particular specimen was attached to an acorn barnacle, Coronula diadema, which was attached to a humpback whale! Rabbit-ear barnacles get their nutrients from the water by filter feeding using their legs as mouth parts, so this arrangement with whales works well for them as they get a free ride from one nutrient-rich part of the ocean to the next. This species gets its common name from the rabbit ear-like appendages.

furry camouflage

Milena Acosta

This Brush rabbit, Sylvilagus bachmani, is housed in the Museum's Mammalogy Collection.

Milena Acosta

Can you spot the brush rabbit in the Museum’s Yosemite diorama?

1 of 1

This Brush rabbit, Sylvilagus bachmani, is housed in the Museum's Mammalogy Collection.

Milena Acosta

Can you spot the brush rabbit in the Museum’s Yosemite diorama?

Milena Acosta

The Brush rabbit, Sylvilagus bachmani, is only found along the west coast of North America between Oregon down to the Southern tip of Baja, and are common in California. Because of its brown and gray fur, the rabbit is easily able to camouflage itself in busy places—especially when being hunted by predators like large birds, bobcats, and snakes. Can you spot the brush rabbit in the Museum’s Yosemite diorama?

Rabbitfishes: Bony and Cartilaginous

Pictured above is Hydrolagus colliei, which is part of a cartilaginous group of fishes that goes by many names, including chimaeras, ratfish, ghost sharks, and rabbitfishes. This group of fishes are related to other cartilaginous fishes, such as sharks, skates, and rays. The majority of chimaeras live in deeper, cooler waters where they eat a variety of food, including crustaceans and mollusks. Females lay eggs, and all species have a venomous dorsal spine that you wouldn’t want to touch!

While chimaeras go by many names, including rabbitfishes, there is another group of bony fishes that are also called rabbitfishes. Unlike the cartilaginous rabbitfishes, fishes in the family Siganidae are shallow-water, herbivorous fishes that live in and near coral reefs. Several species are very colorful and can be found in the aquarium trade, and many are important food fishes. They can be found throughout the Indo-Pacific, and like the cartilaginous rabbitfishes, they also have venomous spines that you want to watch out for.

A bony lattice skull

Milena Acosta

Lagomorph skulls have lattice-like areas that help reduce the impact of hopping.

Milena Acosta

Lagomorphs share a second set of peg-like upper incisors directly behind the first set.

1 of 1

Lagomorph skulls have lattice-like areas that help reduce the impact of hopping.

Milena Acosta

Lagomorphs share a second set of peg-like upper incisors directly behind the first set.

Milena Acosta

All lagomorphs have extensive fenestration in their skulls, where the surface of the bones has spaces and resembles a lattice. This adaptation reduces the impact of hopping by reducing the weight of the skull and making space for fluid and pressure to dissipate during landing and bounding. The other characteristic lagomorphs share is a second set of peg-like upper incisors directly behind the first set.

Origins of the Trickster Rabbit

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Anthropology (Ethnology)

Egungun masquerade headpieces carved in the shape of the West African trickster-rabbit spirit.

Milena Acosta

The African savannah hare, Lepus victoriae, is considered to be the "original Brer Rabbit."

1 of 1

Egungun masquerade headpieces carved in the shape of the West African trickster-rabbit spirit.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County - Anthropology (Ethnology)

The African savannah hare, Lepus victoriae, is considered to be the "original Brer Rabbit."

Milena Acosta

The rabbit is a trickster and a wily character in many West African folktales. When West Africans arrived in North America and the Caribbean, these stories became the foundation of characters like Brer Rabbit and Bugs Bunny. These Egungun masquerade headpieces are carved in the shape of the trickster-rabbit spirit. The headpieces would be worn on the top of the head while the body is obscured with raffia or multicolored clothing with a hidden opening or screen over the eyes to allow the dancer to see. The African savanna hare (Lepus victoriae) found throughout Africa is likely the species that inspired the early folktales. These hares often run in a zig-zag pattern to break the scent trail they are leaving, and these sideways movements are probably why they are considered "wily."

Hunting for Wabbits

Milena Acosta

This Harris’s hawk specimen, Parabuteo unicinctus, is cared for by the Museum's Ornithology Collection.

Milena Acosta

The hawls large feel and talons help them prey on animals, like rabbits and hares!

Milena Acosta

This Harri's hawk falconry helmet was donated to the Museum's Ornithology Collection.

1 of 1

This Harris’s hawk specimen, Parabuteo unicinctus, is cared for by the Museum's Ornithology Collection.

Milena Acosta

The hawls large feel and talons help them prey on animals, like rabbits and hares!

Milena Acosta

This Harri's hawk falconry helmet was donated to the Museum's Ornithology Collection.

Milena Acosta

Rare for raptors, Harris’s hawk (Parabuteo unicinctus), is a social bird known to hunt cooperatively in groups when food is scarce or when taking down larger prey like the desert cottontail and jackrabbits that are heavier than an individual hawk! Owing to this social nature, they make excellent falconry birds and are often used for hunting those prey species. They also have quite large feet and talons for their body size, which also reflects their diet of larger prey animals.

A "Rabbit foot" buzzard

Milena Acosta

The Rough-legged buzzard specimens pictured, Buteo lagopus, are housed in the Ornithology Collection.

Milena Acosta

Compared to Harri's hawks (top), the Rough-legged buzzard (bottom) has more pronounced feathered feet.

1 of 1

The Rough-legged buzzard specimens pictured, Buteo lagopus, are housed in the Ornithology Collection.

Milena Acosta

Compared to Harri's hawks (top), the Rough-legged buzzard (bottom) has more pronounced feathered feet.

Milena Acosta

The Rough-legged buzzard, Buteo lagopus, has legs covered in feathers—hence the species name “rabbit foot”—most likely reflecting their habitat range in the Arctic. The feathered feet are more pronounced next to that of the desert-dwelling Harris’s Hawk. Rough-legged buzzards also feed on smaller rodents, which is why their feet are proportionally smaller when compared to the slightly smaller Harris’s Hawk.

The pika

The American pika, Ochotona princeps, are very vocal and have small bodies (around 8 inches long) and hind feet, only weighing about 6 oz. Pikas are found at high elevations in western North America and live on rocky alpine slopes of mountains. Because they are sensitive to high temperatures and live at the peaks of mountains, they cannot easily migrate as temperatures increase due to global warming. This species is considered a local marker of climate change, with many mountain populations experiencing range retractions or disappearing altogether.

Sea bunny

Milena Acosta

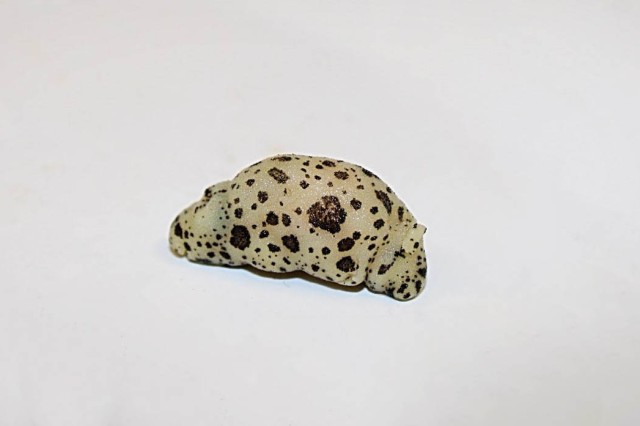

This sea bunny, or Polka-dot nudibranch (Jorunna funebris) is a marine gastropod. It is housed in the Malacology Colllection.

Milena Acosta

The Polka-dot nudibranch varies in size but average size is between 1 and 1.5 inches.

Tine Kinn Kvamme, iNaturalist

When these sea bunnies are alive, their distinct decorated patches are more pronounced along with the rhinophores and gills.

1 of 1

This sea bunny, or Polka-dot nudibranch (Jorunna funebris) is a marine gastropod. It is housed in the Malacology Colllection.

Milena Acosta

The Polka-dot nudibranch varies in size but average size is between 1 and 1.5 inches.

Milena Acosta

When these sea bunnies are alive, their distinct decorated patches are more pronounced along with the rhinophores and gills.

Tine Kinn Kvamme, iNaturalist

Sea bunnies are shell-less marine gastropods called nudibranchs. This species, Jorunna funebris, is also known as the Polka-dot nudibranch due to its distinct decorated patches over its cream-colored body. Like the California sea hare, sea bunnies get their name from their hare-like rhinophores located at the front end of their bodies. Because of their worm-like shape, rhinophores are often nibbled on by fish! Some nudibranchs can protect themselves from such damage by withdrawing into a pocket beneath their skin.

Fossils from "The Rabbit Ranch"

This fossil brachiopod was collected from rocks called the Conejo Volcanics, which formed during a period of intense volcanic activity about 15-17 million years ago. The Conejo Volcanics are found in the Conejo Valley, the northwestern side of the Santa Monica Mountains. A Spanish land grant named the area “Rancho El Conejo” which translates to “The Rabbit Ranch,” referencing the abundant desert cottontail and brush rabbits that lived throughout the area.