story

Published February 27, 2023

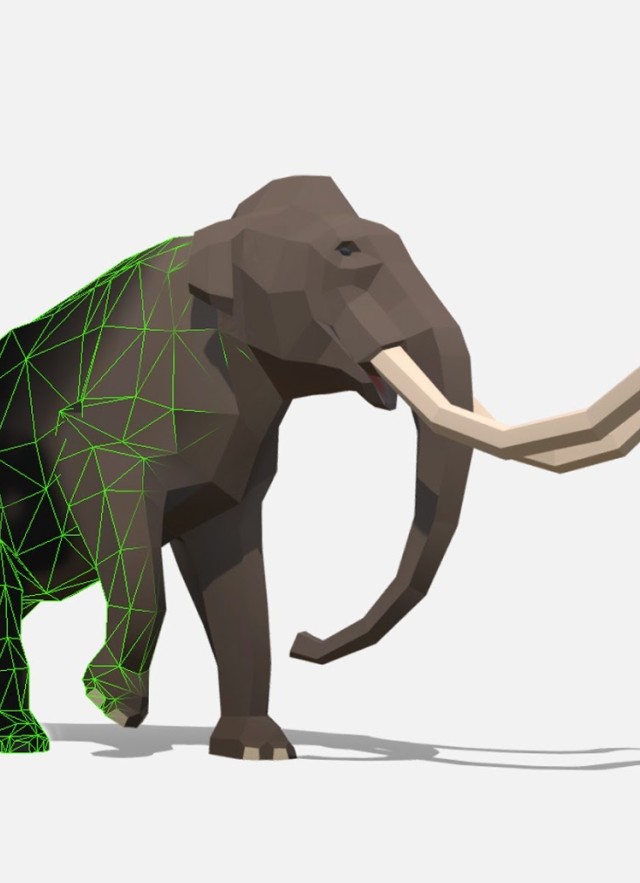

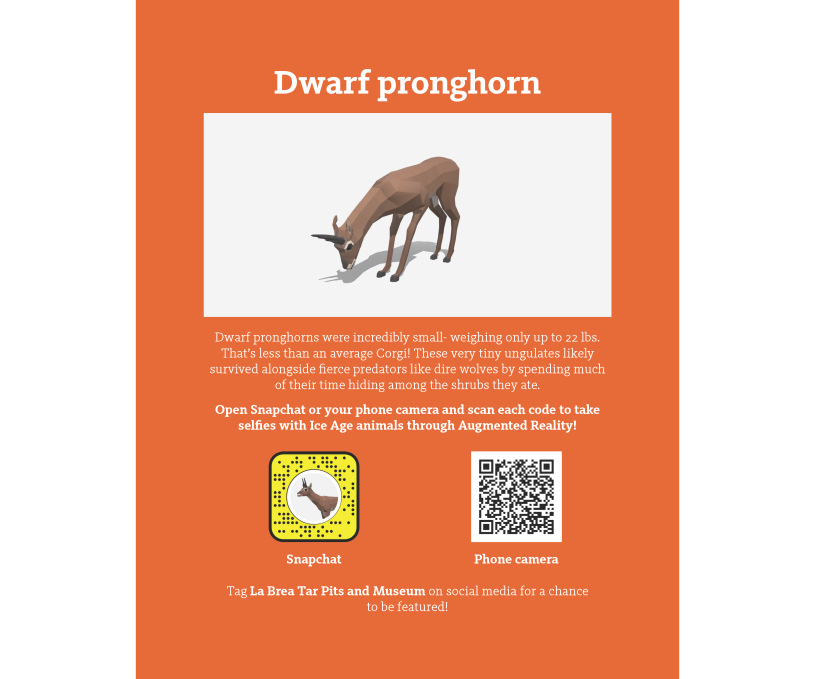

AR, or augmented reality, lets you overlay the physical world with digital creations. For Tar AR, that means low-poly 3D models of scientifically accurate paleoart reconstructions of Ice Age animals found at La Brea Tar Pits, created with support from Snap Inc. With your smartphone’s camera, you can bring any of 13 extinct Ice Age Angelenos back to Hancock Park—from mammoths and mastodons to dire wolves and saber-toothed cats along with the less famous but equally fantastic creatures that prowled L.A. in the last Ice Age—simply by scanning a QR code on any one of the signs (like the one below) throughout the Park.

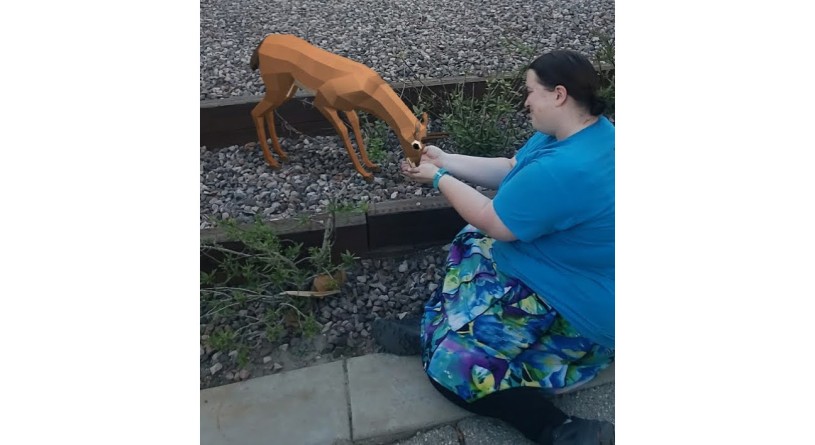

“I’ll hear the cutesy sounds of kids with a small dog, and crane my neck to catch a peek,” says La Brea Tar Pits Senior Fossil Preparator Laura Tewksbury. What the kids (and adults) are actually cooing at is Capromeryx the dwarf pronghorn, an animal that looked somehwat like a deer but weighed less than your average Corgi.

Tewksbury is lucky enough to have the pronghorn sign posted right outside her working area, and people have definitely noticed. “It’s getting a lot of love, students trying to hug it, trying not to step on it.”

This kind of activation of the dig space is particularly fruitful with something as commonly found as the tiny pronghorn. While discussing the warm reception the digital dwarf pronghorn has been getting, Tewksbury produces one of the two toes excavated from the asphalt that week, and just like that, a crowd begins to form. The AR animals are attracting real people to real fossils—and the science happening at the museum.

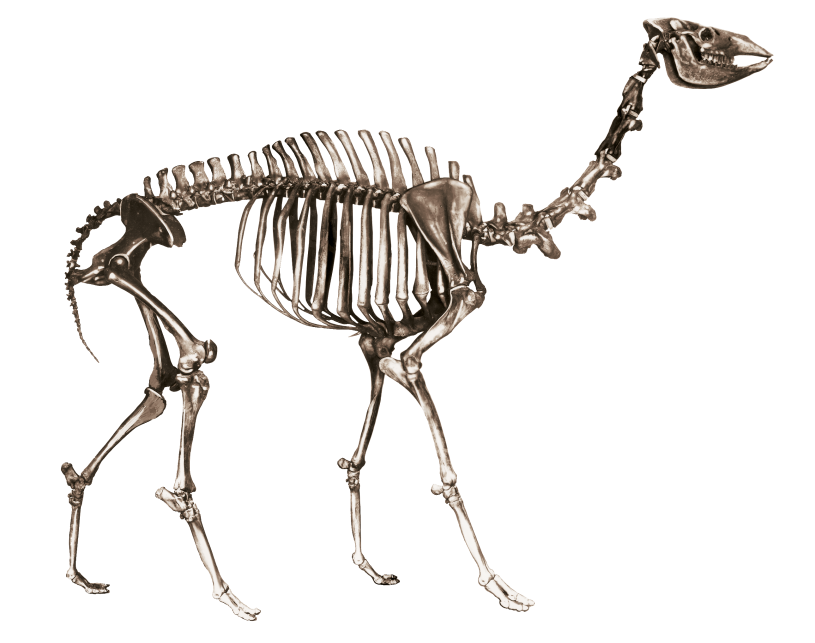

“I want people to get a sense of what these creatures actually looked like with skin on, how they moved, how big they were,” says Danaan DeNeve Weeks, La Brea Tar Pits Postdoctoral Research Scientist and one of the brains behind the project. “It's easy to feel a little dissociated from a skeleton, but with the AR animals, you can really get a feel for what the living creature would have been like. It's easier to picture them walking around at La Brea and getting buried beneath your feet.”

AR is still new on the museum scene, so DeNeve Weeks and their colleagues have been testing how to best bring this digital tool into the physical museum space–and making sure visitors can figure it all out. They’ve been exploring how effective the technology is at connecting visitors with museum science, and while data is still being collected and analyzed, things are looking good. “People seem to be loving the signs. They've only been out a few weeks, so people are still discovering them, but I see someone trying to take a selfie with one of the AR animals almost every time I walk through the Park.”

The low-poly creations bring together the most accurate depiction of these animals based on what we know now (one of the great things about science is that we’re always learning new things). In fact, their measurements are based on their fossil counterparts on display at the museum. Enough dwarf pronghorn bones have been recovered at La Brea Tar Pits to produce a complete skeleton and their cousins, the regular-sized pronghorns, are still alive and kicking (really hard—do not approach!). Depictions of these animals have been pretty stable over time.

Other animals have only been recovered much less often and in smaller pieces. Their depictions have evolved as more of those pieces have been discovered and scientific analysis continues to improve. Take the largest meat-eating mammal to ever walk on land: the short-faced bear.

If you saw something bigger than a polar bear loping down Wilshire, the first adjective to come to mind probably wouldn’t be ‘short-faced.’ These extinct bears were definitely huge, but past paleoart representations have been heavy on imagination. Only portions of these animals have been recovered at the Tar Pits—not nearly enough to create a whole skeleton—and current thinking suggests that these big bears varied in size across the continent. The low-poly predator currently stalking the Tar Pits reflects the most up-to-date image of this massive meat eater given our limited evidence.

“It’s a fascinating animal that we don’t know quite as much about as the others,” says DeNeve Weeks. They point out that these bears—while terrifyingly huge—were probably lankier than the fearsome statue towering over guests in the museum.

With only 30 individuals discovered in the entire history of La BreaTar Pits, it’s difficult to say exactly, so something with less detail may be more accurate. Analysis of the bears’ teeth conducted by the museum’s research associates suggests that these bears had omnivorous diets similar to their cousins in South America today, the tiny-by-comparison spectacled bear. The sole surviving species of a previously diverse group that once ranged across the continent, spectacled bears ‘spectacles’ refer to distinct, lighter-colored markings on their faces and chests. The living bears ‘spectacles’ suggests that facial markings were more likely than not, so the paleontologist behind the digital recreation included white facial markings not seen on earlier representations of short-faced bears.

“We know a lot about many of these animals, but there's a whole lot that we still don't know, and may never know,” says DeNeve Weeks. “Another great example of this is that we have no idea whether male American lions had manes. The low-poly aesthetic allows us to depict these animals in a way that is really visually impactful, and accurate as far as we know right now, but isn't detailed past the point of our knowledge. With the low-poly depictions we don't have to try to invent details that we may discover in ten years are wrong.”

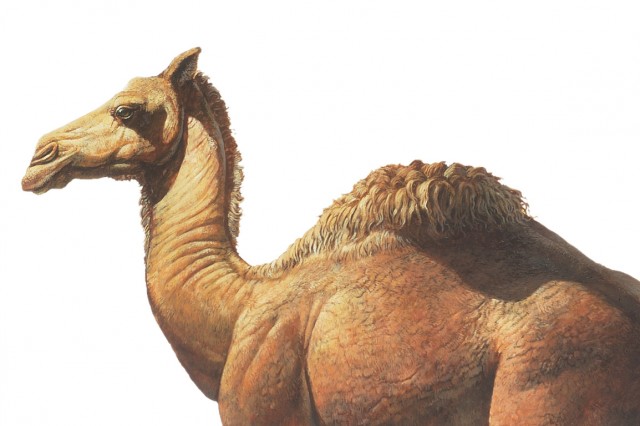

The Western camel has something like a mini-hump despite its impressive size; the fatty tissue that makes up modern camels’ single or double humps wouldn’t survive fossilization in the asphalt, so they split the difference with a more modest mound. Visitors can find a fully articulated skeleton on display inside the museum alongside other immense herbivores that only graze the area today in AR form.

Though associated with the Middle East and North Africa, camels actually got their start in North America. La Brea Tar Pits can be like that though, subverting our understanding of animal life on the planet. We might associate big cats and large herbivores with places like the Serengeti in Africa, but many of their often weirder and larger cousins were L.A. locals before humans arrived on the scene. Tar AR puts them back in the landscape, helping visitors understand just how powerful human impacts have already been.

“The environment of L.A. was very different 15,000 years ago, and the climate in this particular part of the world was only a little different,” says DeNeve Weeks. “I think it's a really good illustration of how climate doesn't have to change that much when that change is coupled with human impacts that affect how animals are able to interact with the landscape.”

While Tar Pits fossils are invaluable to researchers and moving for visitors, they never move on their own. AR lets these animals move in the world, instantly connecting visitors with science’s best understanding of the surprising ways some of them got around. The dire wolf lopes, the mastodon stomps, and the ground sloths move in their own special way.

“My favorite is the Shasta ground sloth. They’re just so weird and cute,” says DeNeve Weeks. These sloths actually walked on their front knuckles and the sides of their back feet, an endearingly strange way to step that’s difficult to picture with an articulated skeleton alone: “I think of them as having a sort of swaggering lumber.” The low poly model brings that weird walk to life. At around 550 pounds, the Shasta ground sloth is one of the smallest known ground sloths.

Harlan's ground sloth weighed in at more than 2,000 pounds. These bulky beasts had more than size on their side. Sloths in this family had bony plates under their skin called osteoderms to dissuade any saber-toothed cats whose eyes were bigger than their stomachs. Unlike the unknowable hump of the Western camel, these osteoderms have been recovered from the Tar Pits, just one of the ways that fossils fuel our understanding of just how weird ground sloths were.

Tar AR lets guests see the Tar Pits in a totally new way, and this is only the start. “A full AR experience is coming soon, where visitors will be able to watch Pleistocene animals interact with each other and move across the lawn, culminating in an entrapment event where several creatures become mired in an asphalt seep (tar pit),” says DeNeve Weeks. “We hope that this experience helps museum and park visitors understand how our fossils got here, and a bit more about what the environment of Ice Age L.A. was like.”

The fossil fun doesn’t stop when you leave Hancock Park. While there’s no better place to see these Ice Age Angelenos than La Brea Tar Pits, they weren’t limited to Miracle Mile then, so it’s fitting that guests can bring these animals anywhere their smartphones go now. Once you’ve scanned the code (look for the orange placards in the Park), you can bring these extinct animals back to life anywhere you’d like. So, get ready to see ground sloths at LAX, bison on the 405, dire wolves at the dog park, and maybe some mammoths at MOCA.