Smilodon, Saber-Tooths, and Tigers…Oh My!

How Smilodon became saber-toothed tigers—and why they're really saber-toothed cats

Published August 29, 2023

One of the most common questions asked at La Brea Tar Pits is why we don’t call Smilodon a "Saber-toothed Tiger.” There is no single explanation for this, rather it was a series of cultural associations which resulted in this common, but inaccurate name.

The earliest naturalists, paleontologists, and artists were trying to understand these extinct Felids, the Family that all cats belong to. The group we call Saber-toothed Cats, the Machairodontinae, is a subfamily of the Felidae that went extinct by the end of the Pleistocene. Tigers (Panthera tigris) belong to the subfamily Pantherinae, which includes all the true big cats such as lions, leopards, jaguars, and snow leopards.

What IS A Saber Tooth Tiger?

Many of the common names we use for cats have broad associations such as “panther” “wild cat” or “leopard” (such as “snow leopard” and “clouded leopard”) and these names do not indicate close relationships but instead are more descriptive of what the animal looks like. When fossils of Saber-toothed Cats were discovered, scientists attempted to compare them with animals that they were more familiar with. Tigers are amongst the oldest of the big cats, they are the largest cats alive today, and have the biggest teeth.

The first Saber-toothed Cat fossils were found in places like Turkey, Brazil, and North America. Some of these fossils were misidentified as other carnivores at first such as hyenas and bears, and mistaken identities became a recurring theme with these strange felines. Early scientists called them Machairodus, a “wastebasket taxon” that most Saber-toothed Cats were lumped into. When a Smilodon tooth was discovered at the Hancock Asphalt Quarry at Rancho La Brea in 1875, it was first identified as a “species of Machairodus” by geologist William Denton.

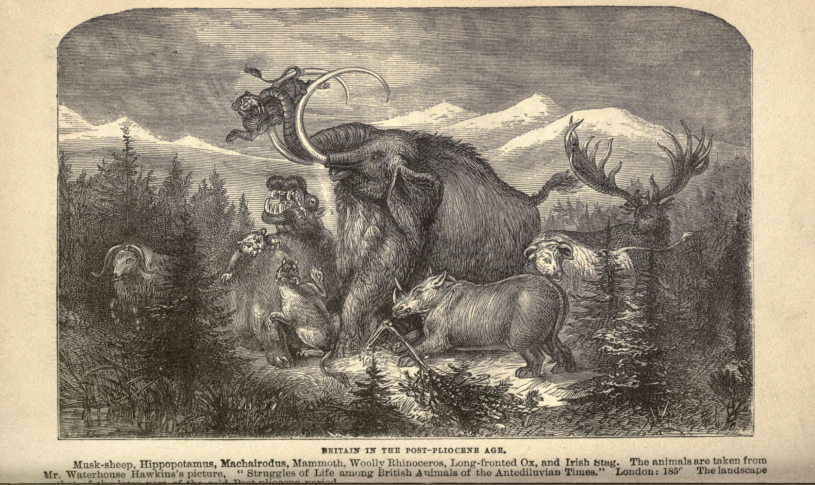

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, an early naturalist who depicted dinosaurs and other extinct animals in sculpture at an exhibition at the Crystal Palace, also made his attempt to depict these foreign-looking felines in the mid 19th century. His lithograph “Struggles of Life Among the British Animals of Primeval Times” from 1853 depicts two Saber-toothed Cats attacking an extinct hippopotamus, and a third being swung around by the trunk of a mammoth. These were labeled “Scimitar-toothed Lions” and nearby a “cave tiger” stalks an extinct ox. So the labels of “Saber-toothed Tiger” and “cave lion” in some of these early images are reversed.

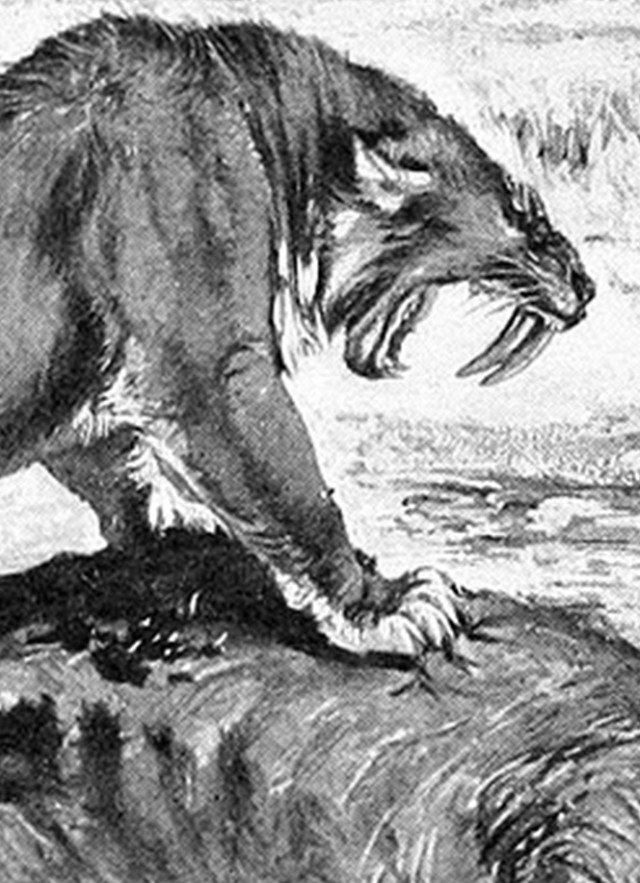

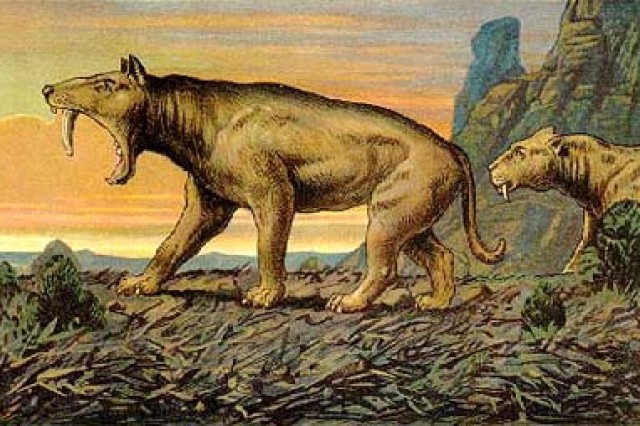

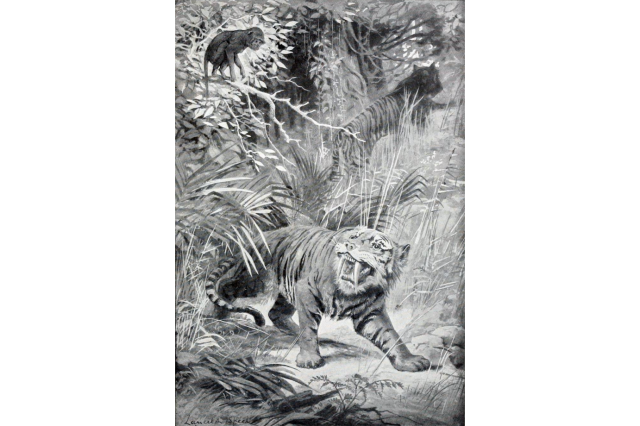

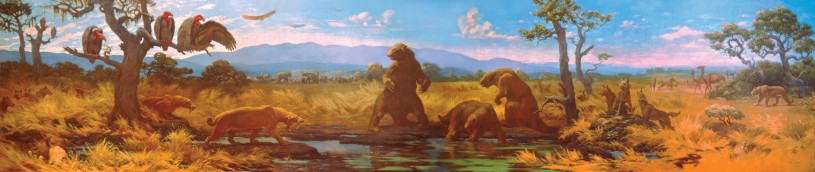

Late 19th and early 20th century artists began depicting extinct Saber-toothed Cats as tigers, crouching and stalking prey because some of them were assumed to be ambush predators as well. These scientists were basing their assumptions on what modern animals they had to compare them to. For example, the Thylacine sometimes called a “Tasmanian tiger” with its stripes and large jaw gape. Even though it was a marsupial, and was still alive at the time of many of these earliest works of paleoart, they still were assigned the label of “tiger” because of their stripes, even though they had no close genetic relationship.

“Sabellowe” F. John, Germany 1903

"Sabre-toothed Tiger and Cave Lion" Alice B Woodward, 1910

Early restoration of Machairodus, a genus of saber-toothed cat from the late Miocene, with tiger-like markings. Lancelot Speed, 1905

1 of 1

“Sabellowe” F. John, Germany 1903

"Sabre-toothed Tiger and Cave Lion" Alice B Woodward, 1910

Early restoration of Machairodus, a genus of saber-toothed cat from the late Miocene, with tiger-like markings. Lancelot Speed, 1905

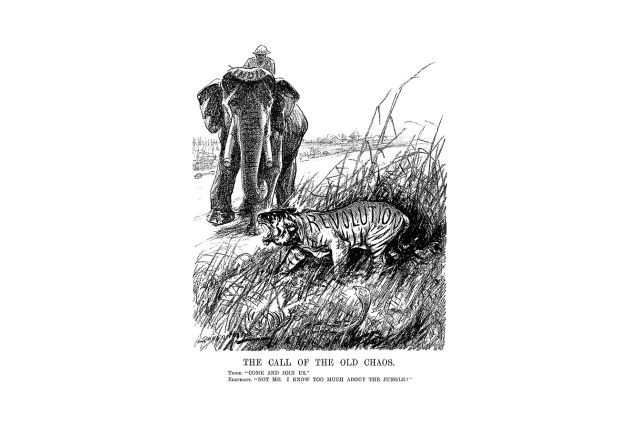

The European naturalists, scientists, and artists of the 19th century were part of imperialist systems that collected specimens from around the globe. World powers of the day like the British Empire collected tigers from hunting expeditions, and taxidermists of the time gave these animals a distinctive crouching posture that mimicked the political cartoons of the era. These cartoons were rife with colonial imagery and subtext, but they associated tigers with a primordial or primitive nature which they also associated with their colonial subjects. European scientists were studying these animals and putting them into Linnaean classifications just as they were with fossils, trying to piece together clues to understand their relationships with other animals. The artists that accompanied these scientists may have based their paleoart on the interpretations of these crouched, taxidermied tigers and filled their depictions with their cultural biases.

Cartoon referencing the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, entitled "The New Year's Gift", India is represented by a cowed tiger. Punch magazine, 1858

Bengal Tiger specimen from Nepal, given to the Natural Museum of Ireland by King George V in 1913

Punch magazine, 1840s-50s

1 of 1

Cartoon referencing the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, entitled "The New Year's Gift", India is represented by a cowed tiger. Punch magazine, 1858

Bengal Tiger specimen from Nepal, given to the Natural Museum of Ireland by King George V in 1913

Punch magazine, 1840s-50s

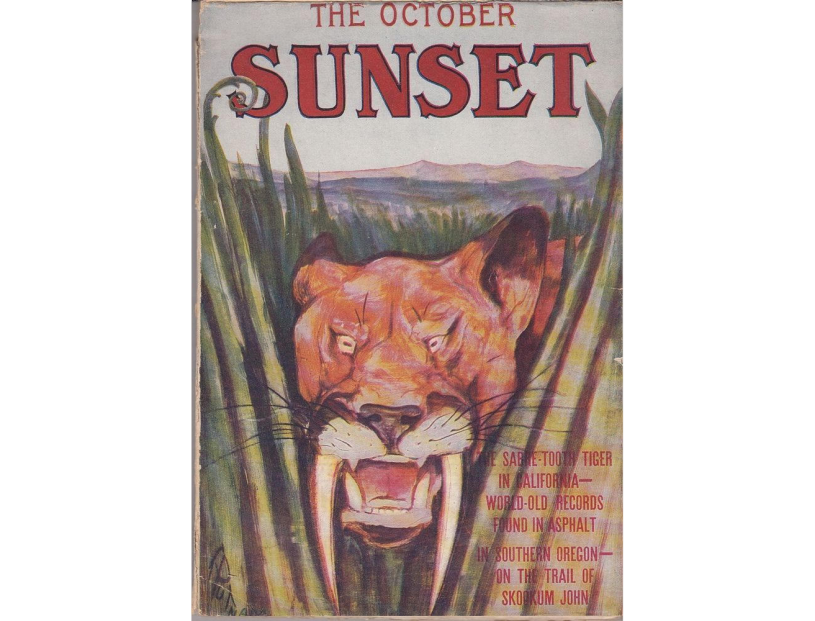

These early images of Saber-toothed Cats became more standardized in the early 20th century, cementing the association of Saber-toothed Cats and tigers for many years. One of the main reasons for this is that it is easier and more pleasing to say “Saber-toothed Tiger” because of the alliteration and it becomes a recognizable mnemonic device. Images and sounds can reinforce these ideas, and species recognition plays a prominent role. Tigers are the most recognizable cats visually, and as a result the association helps us recognize and distinguish this unique cat from the past. Media in the form of books, movies, television, and video games can perpetuate this stereotype, or allow for creative license for artists to interpret them in new ways.

La Brea Tar Pits have long been depicting Smilodon with fur that is neutral. No mane, color, or coat pattern was used in early images besides a tawny color similar to a lion or cougar. More recent depictions from the 1970s and onward tend to favor a spotted coat, which is more common in the world of cats for ambush hunters. Smilodon has long been a symbol of the Tar Pits campus because that's where the fossils had been displayed for decades until the then-new Page Museum of La Brea Discoveries was opened in 1977, where the Smilodon became an icon for a new era of Tar Pits exploration.

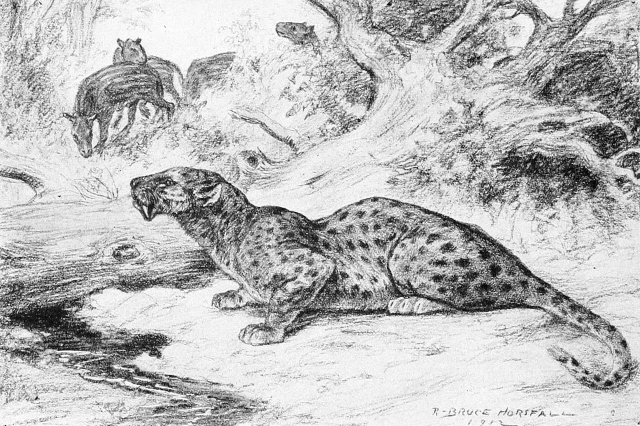

Restoration of H. primaevus by Robert Bruce Horsfall, 1913

Holophoneus occidentalis,a Nimravid, not a “true” saber-toothed cat, artist unknown, 1894/1898?

Popular Science Monthly Volume 53

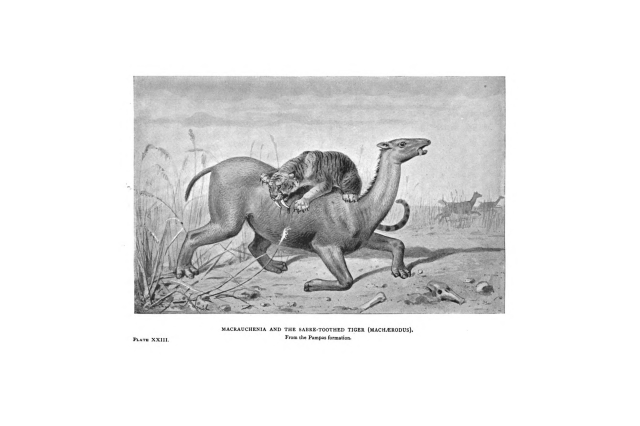

Macruchenia patagonia (Miocene to Pleistocene) attacked by Smilodon populator (Pliocene to Pleistocene). Macrauchenia and the sabre-toothed tiger, Machaerodus.

Print after illustration by Joseph Smith from Henry Neville Hutchinson's Creatures of Other Days, Popular studies in Paleontology, Chapman and Hall, London, 1896.

1 of 1

Restoration of H. primaevus by Robert Bruce Horsfall, 1913

Holophoneus occidentalis,a Nimravid, not a “true” saber-toothed cat, artist unknown, 1894/1898?

Popular Science Monthly Volume 53

Macruchenia patagonia (Miocene to Pleistocene) attacked by Smilodon populator (Pliocene to Pleistocene). Macrauchenia and the sabre-toothed tiger, Machaerodus.

Print after illustration by Joseph Smith from Henry Neville Hutchinson's Creatures of Other Days, Popular studies in Paleontology, Chapman and Hall, London, 1896.

Today, the term sticks, much like the sticky tar where over 2,500 Smilodon have been uncovered from the asphaltic deposits at La Brea Tar Pits. People continue to use terms like “Saber-toothed Tiger'' because it's easy and fun to say, and they are an easily recognizable animal from the Ice Age, just like tigers are easy to spot in the media today.

The life-sized saber-toothed cat puppet, Cali, and juvenile saber-toothed kitten puppet, Nibbles, perform regularly as part of the Ice Age Encounters show at the museum.

An augmented reality saber-toothed cat in front of the museum at La Brea Tar Pits. This depiction is one of a suite of low-poly 3D models of scientifically accurate paleoart reconstructions of Ice Age animals in the Tar AR experience.

An animatronic saber-toothed cat defends its prey at the museum at La Brea Tar Pits.

1 of 1

The life-sized saber-toothed cat puppet, Cali, and juvenile saber-toothed kitten puppet, Nibbles, perform regularly as part of the Ice Age Encounters show at the museum.

An augmented reality saber-toothed cat in front of the museum at La Brea Tar Pits. This depiction is one of a suite of low-poly 3D models of scientifically accurate paleoart reconstructions of Ice Age animals in the Tar AR experience.

An animatronic saber-toothed cat defends its prey at the museum at La Brea Tar Pits.